Overview

Vocal cord paralysis is a condition that causes the loss of control of the muscles that control the voice. It happens when the nerve impulses to the voice box, also called the larynx, are disrupted. This results in paralysis of the vocal cord muscles.

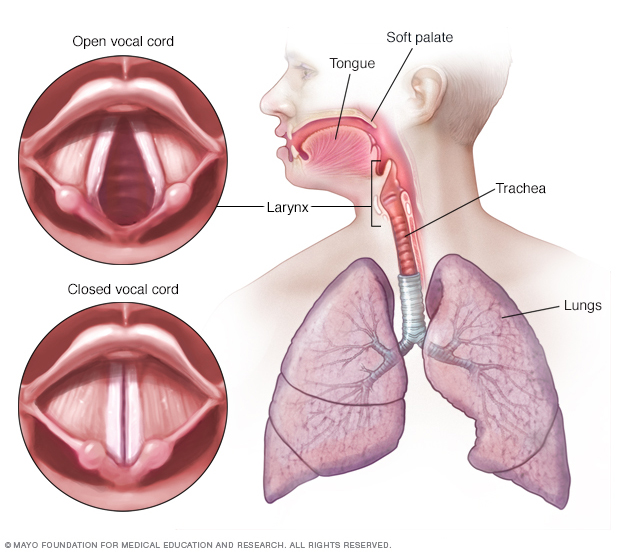

Vocal cord paralysis can make it hard to speak and even breathe. The vocal cords, also called vocal folds, do more than just produce sound. They also protect the airway. They prevent food, drink and even saliva from entering the windpipe and causing a person to choke.

Possible causes of vocal cord paralysis include nerve damage during surgery, viral infections and certain cancers. Treatment for vocal cord paralysis usually involves surgery, and sometimes voice therapy.

Symptoms

Vocal cord paralysis usually involves the loss of control of only one vocal cord. Paralysis of both vocal cords is a rare but serious condition. This can make it hard to speak and can cause trouble with breathing and swallowing.

The vocal cords are two flexible bands of muscle tissue that sit at the entrance to the windpipe, also known as the trachea. When speaking, the bands come together and vibrate to make sound. The rest of the time, the vocal cords are relaxed in an open position so that you can breathe.

Symptoms of vocal cord paralysis may include:

- A breathy quality to the voice.

- Hoarseness.

- Noisy breathing.

- Shortness of breath.

- Loss of vocal pitch.

- Choking or coughing while swallowing food, drink or saliva.

- The need to take several breaths while speaking.

- Inability to speak loudly.

- Loss of a gag reflex.

- Ineffective coughing.

- Frequent throat clearing.

When to see a doctor

Contact your healthcare professional if you have a hoarse voice that can't be explained and that lasts for more than 2 to 4 weeks. Also see your healthcare professional if you notice any voice changes or discomfort.

Causes

Vocal cord paralysis happens when nerve impulses to the voice box, known as the larynx, are disrupted. This causes the muscle to become paralyzed. Often the exact cause of vocal cord paralysis isn't known. But some known causes may include:

- Injury to the vocal cord during surgery. Surgery on or near the neck or upper chest can result in damage to the nerves that serve the voice box. Surgeries that carry a risk of damage include surgeries to the thyroid or parathyroid glands, esophagus, neck, and chest.

- Neck or chest injury. Trauma to the neck or chest may injure the nerves that serve the vocal cords or the voice box itself.

- Stroke. A stroke interrupts blood flow in the brain and may damage the part of the brain that sends messages to the voice box.

- Tumors. Tumors, both cancerous and noncancerous, can grow in or around the muscles, cartilage or nerves controlling the function of the voice box. This can cause vocal cord paralysis.

- Infections. Some infections, such as Lyme disease, Epstein-Barr virus and herpes, can cause inflammation and directly damage the nerves in the voice box. There's some evidence that infection with COVID-19 may cause vocal cord paralysis.

- Neurological conditions. Certain neurological conditions, such as multiple sclerosis or Parkinson's disease, can lead to vocal cord paralysis.

Risk factors

Risk factors for vocal cord paralysis include:

- Having throat or chest surgery. People who need surgery on their thyroid, throat or upper chest have an increased risk of vocal cord nerve damage. Sometimes the breathing tubes used in surgery or to help people breathe when they're having serious respiratory trouble can damage the vocal cord nerves.

- Having a neurological condition. People with certain neurological conditions — such as Parkinson's disease or multiple sclerosis — are more likely to develop vocal cord weakness or paralysis.

Complications

Breathing problems associated with vocal cord paralysis may be so mild that you just have a hoarse-sounding voice. Or they can be so serious that they're life-threatening.

Vocal cord paralysis keeps the opening to the airway from completely opening or closing. This can cause someone to choke on or inhale food or liquid, known as aspiration. Aspiration that leads to severe pneumonia is rare but serious and requires immediate medical care.

Diagnosis

To diagnose vocal cord paralysis, your healthcare professional asks about your symptoms and lifestyle. Your care professional also listens to your voice and asks how long you've had voice changes. You also may need the following tests:

-

Laryngoscopy. Your healthcare professional looks at your vocal cords using a mirror or a thin, flexible tube known as a laryngoscope or endoscope, or both. You also may have a test called videostrobolaryngoscopy. It uses a special scope that contains a tiny camera at its tip or a larger camera connected to the scope's viewing piece.

These special high-magnification endoscopes allow your healthcare professional to view your vocal cords directly or on a video monitor. The tests reveal the movement and position of the vocal cords. This can tell your healthcare professional whether one or both vocal cords are affected.

-

Laryngeal electromyography. This test measures the electrical currents in your voice box muscles. To do this, small needles are inserted into the vocal cord muscles through the skin of the neck.

This test isn't used to guide treatment, but it may give an estimate about how well you may recover. This test is most useful when it's done between six weeks and six months after your symptoms began.

- Blood tests and scans. Several diseases may cause nerve injuries. You may need additional tests to find the cause of the paralysis. Tests may include bloodwork, X-rays, MRI or CT scans.

Treatment

Treatment of vocal cord paralysis depends on the cause, how serious the symptoms are and when symptoms began. Treatment may include voice therapy, bulk injections, surgery or a combination of treatments.

In some instances, you may get better without surgical treatment. For this reason, your healthcare team may delay permanent surgery for at least a year from the beginning of your vocal cord paralysis.

However, surgical treatment with various bulk injections is often done within the first three months of voice loss.

During the waiting period for surgery, you may get voice therapy to help keep you from using your voice improperly while the nerves heal.

Voice therapy

Voice therapy sessions involve exercises or other activities to strengthen your vocal cords and help improve breath control during speech. Voice therapy also can prevent tension in muscles around the paralyzed vocal cord or cords, and protect your airway during swallowing. Voice therapy may be the only treatment needed if the paralysis occurs in an area that doesn't require additional bulk or repositioning.

Surgery

If your vocal cord paralysis symptoms don't fully recover on their own, you may need surgery to improve your ability to speak and to swallow.

Surgical options include:

- Bulk injection. Paralysis of the nerve to your vocal cord will probably leave the vocal cord muscle thin and weak. A doctor who specializes in disorders of the larynx, known as a laryngologist, may add bulk to the paralyzed vocal cord. This is done by injecting the vocal cord with a substance such as body fat, collagen or another approved filler substance. This added bulk brings the affected vocal cord closer to the middle of the voice box. Then the functioning vocal cord can make closer contact with the paralyzed cord when you speak, swallow or cough.

- Structural implants. This procedure relies on the use of an implant in the larynx to reposition the vocal cord. The procedure also is known as thyroplasty, medialization laryngoplasty or laryngeal framework surgery. Rarely, people who have this surgery may need to have a second surgery to reposition the implant.

- Vocal cord repositioning. In this procedure, a surgeon moves a window of your own tissue from the outside of your voice box inward, pushing the paralyzed vocal cord toward the middle of your voice box. This allows your functioning vocal cord to better vibrate against the paralyzed vocal cord.

- Replacing the damaged nerve, known as reinnervation. In this surgery, a healthy nerve is moved from a different area of the neck to replace the damaged vocal cord. It can take as long as 6 to 9 months before your voice gets better. This surgery is sometimes combined with a bulk injection.

-

Tracheotomy. If both of your vocal cords are paralyzed and positioned closely together, your airflow will be decreased. This causes a lot of trouble breathing and requires a surgery called a tracheotomy.

A cut is made in the front of your neck to create an opening in the windpipe, also known as the trachea. A breathing tube is inserted, allowing air to bypass the vocal cords.

Emerging treatments

Linking the vocal cords to another source of electrical stimulation may restore opening and closing of the vocal cords that can't move. Other sources of electrical stimulation might be a nerve from another part of the body or a device similar to a cardiac pacemaker. Researchers continue to study this and other options.

Coping and support

Vocal cord paralysis can be frustrating and affect your daily life. It can be hard to communicate with other people. A speech therapist can help you develop the skills you need to communicate.

Even if you're not able to get back the voice you once had, voice therapy can help you learn effective ways to make up for it. In addition, a speech-language pathologist can teach you how to use your voice without causing further damage to the vocal cords.

Preparing for an appointment

You're likely to first see your healthcare professional about vocal cord paralysis. But if both vocal cords are paralyzed, you'll probably first be seen in a hospital emergency department.

After the initial assessment, you'll likely be referred to a doctor who specializes in ear, nose and throat conditions. You also may be referred to a speech-language pathologist for voice assessment and therapy.

It's helpful to arrive well prepared for your appointment. Here's some information to help you get ready and what to expect.

What you can do

- Write down any symptoms you're experiencing, including any that may not seem related to the reason for which you scheduled the appointment.

- Write down key personal information, including any major stresses or recent illnesses or life changes.

- Make a list of all medicines, vitamins or supplements that you're taking, including the dose of each.

- Ask a family member or friend to come with you, if possible. Sometimes it can be difficult to remember all of the information provided to you during an appointment. Someone who is with you may remember something that you missed or forgot.

- Write down questions to ask your healthcare team.

Your time with your healthcare professional may be limited. Preparing a list of questions can help you make the most of your time together. For vocal cord paralysis, some basic questions to ask include:

- What's the most likely cause of my vocal cord paralysis?

- What kinds of tests do I need? Do these tests require any special preparation?

- Is this condition temporary, or will my vocal cords always be paralyzed?

- What treatments are available, and which do you recommend?

- What types of side effects can I expect from treatment?

- Are there any alternatives to the treatment that you're suggesting?

- Are there any restrictions on using my voice after treatment? If so, for how long?

- Will I be able to talk or sing after treatment?

- Are there any brochures or other printed material that I can take home with me?

In addition to the questions that you've prepared to ask, don't hesitate to ask any additional questions that occur to you during your appointment.

What to expect from your doctor

Your healthcare professional is likely to ask you a number of questions, such as:

- When did your symptoms start?

- Did any special events or circumstances happen before or at the same time that your symptoms developed?

- Have you received any treatment yet?

- Have your symptoms been continuous or do they come and go?

- How are your symptoms affecting your lifestyle?

- Does anything seem to improve your symptoms?

- What, if anything, appears to worsen your symptoms?

- Do you have any other medical conditions?

© 1998-2026 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use