Overview

Vaginal cancer is a growth of cells that starts in the vagina. The cells multiply quickly and can invade and destroy healthy body tissue.

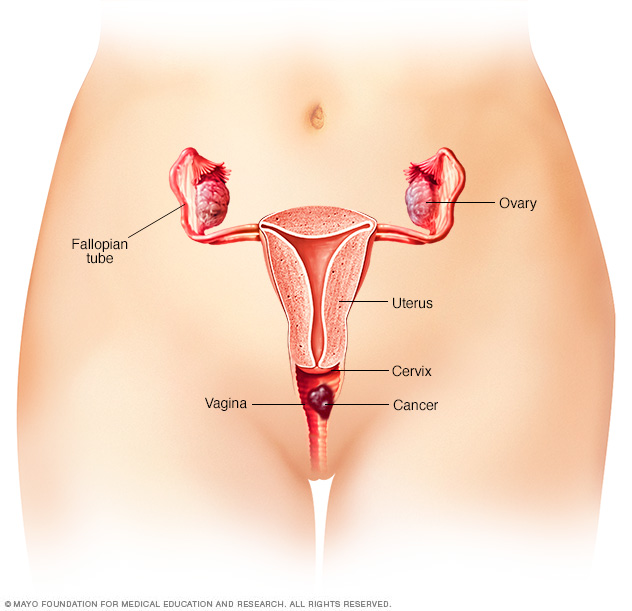

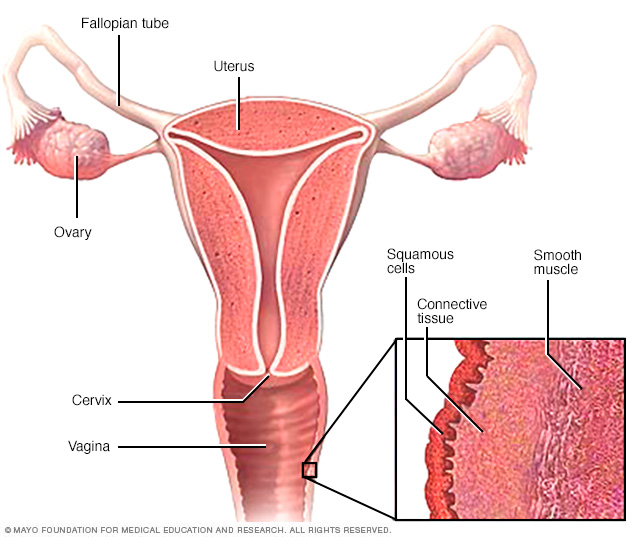

The vagina is part of the female reproductive system. It's a muscular tube that connects the uterus with the outer genitals. The vagina is sometimes called the birth canal.

Cancer that begins in the vagina is rare. Most cancer that happens in the vagina starts somewhere else and spreads to the vagina.

Vaginal cancer that's diagnosed when it's confined to the vagina has the best chance for a cure. When the cancer spreads beyond the vagina, it's much harder to treat.

Symptoms

Vaginal cancer may not cause any symptoms at first. As it grows, vaginal cancer may cause signs and symptoms, such as:

- Vaginal bleeding that isn't typical, such as after menopause or after sex.

- Vaginal discharge.

- A lump or mass in the vagina.

- Painful urination.

- Frequent urination.

- Constipation.

- Pelvic pain.

When to see a doctor

Make an appointment with a doctor or other healthcare professional if you have any persistent symptoms that worry you.

Causes

Vaginal cancer begins when cells in the vagina develop changes in their DNA. A cell's DNA holds the instructions that tell a cell what to do. In healthy cells, the DNA gives instructions to grow and multiply at a set rate. The instructions tell the cells to die at a set time. In cancer cells, the DNA changes give different instructions. The changes tell the cancer cells to make many more cells quickly. Cancer cells can keep living when healthy cells would die. This causes too many cells.

The cancer cells might form a mass called a tumor. The tumor can grow to invade and destroy healthy body tissue. In time, cancer cells can break away and spread to other parts of the body. When cancer spreads, it's called metastatic cancer.

Most DNA changes that lead to vaginal cancers are thought to be caused by human papillomavirus, also called HPV. HPV is a common virus that's passed through sexual contact. For most people, the virus never causes problems. It usually goes away on its own. For some, though, the virus can cause changes in the cells that may lead to cancer.

Types of vaginal cancer

Vaginal cancer is divided into different types based on the type of cells affected. Vaginal cancer types include:

- Vaginal squamous cell carcinoma, which begins in thin, flat cells called squamous cells. The squamous cells line the surface of the vagina. This is the most common type.

- Vaginal adenocarcinoma, which begins in the glandular cells on the surface of the vagina. This is a rare type of vaginal cancer. It's linked to a medicine called diethylstilbestrol that was once used to prevent miscarriage.

- Vaginal melanoma, which begins in the pigment-producing cells, called melanocytes. This type is very rare.

- Vaginal sarcoma, which begins in the connective tissue cells or muscles cells in the walls of the vagina. This type is very rare.

Risk factors

Factors that may increase your risk of vaginal cancer include:

Increasing age

The risk of vaginal cancer increases with age. Vaginal cancer happens most often in older adults.

Exposure to human papillomavirus

Human papillomavirus, also called HPV, is a common virus that's passed through sexual contact. HPV is thought to cause many types of cancer, including vaginal cancer. For most people, HPV infection goes away on its own and never causes any problems. But for some, HPV can cause changes in the cells of the vagina that increase the risk of cancer.

Smoking

Smoking tobacco increases the risk of vaginal cancer.

Exposure to miscarriage prevention medicine

If your parent took a medicine called diethylstilbestrol while pregnant, your risk of vaginal cancer might be increased. Diethylstilbestrol, also called DES, was once used to prevent miscarriage. It's linked to a type of vaginal cancer called clear cell adenocarcinoma.

Complications

Vaginal cancer can spread to other parts of the body. It most often spreads to the lungs, liver and bones. When cancer spreads, it's called metastatic cancer.

Prevention

There is no sure way to prevent vaginal cancer. However, you may lower your risk if you:

Seek out regular pelvic exams and Pap tests

Regular pelvic exams and Pap tests are used to look for signs of cervical cancer. Sometimes vaginal cancer is found during these tests. Ask your healthcare team how often you should undergo cervical cancer screening tests and which tests are best for you.

Consider the HPV vaccine

Receiving a shot to prevent HPV infection may lower the risk of vaginal cancer and other HPV-related cancers. Ask your healthcare team whether an HPV vaccine is right for you.

Diagnosis

Tests and procedures used to diagnose vaginal cancer include:

-

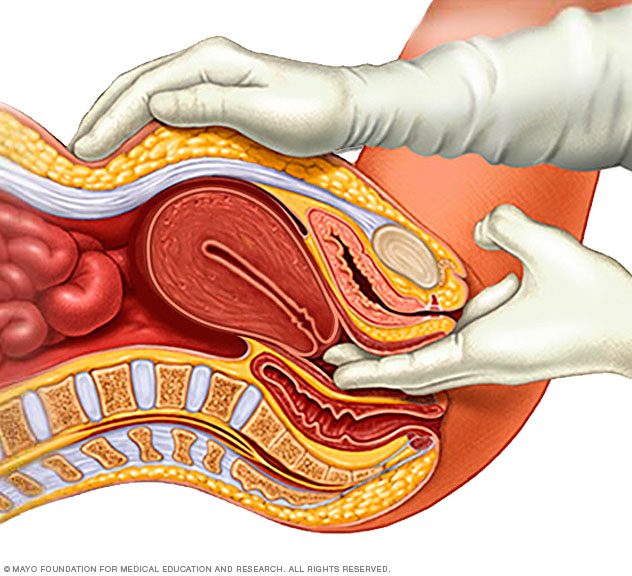

Pelvic exam. A pelvic exam allows a healthcare professional to inspect the reproductive organs. It's often done during a regular checkup. But it might be needed if you have symptoms of vaginal cancer.

During the exam, the healthcare professional carefully inspects the outer genitals. The health professional inserts two fingers of one hand into the vagina. At the same time, that person's other hand presses on the belly to feel the uterus and ovaries. A device called a speculum is inserted into the vagina. The device opens the vaginal canal so the health professional can look for changes in the vagina and cervix. Changes could be signs of cancer or other problems.

- Inspecting the vagina with a magnifying instrument. Colposcopy is an exam to look at the vagina with a special lighted magnifying instrument. Colposcopy helps to magnify the surface of the vagina to look for any changes that might be cancerous.

- Removing a sample of vaginal tissue for testing. A biopsy is a procedure to remove a sample of tissue to test for cancer cells. Often, a biopsy is done during a pelvic exam or a colposcopy exam. The tissue sample is sent to a lab for testing.

Staging

If you're found to have vaginal cancer, your healthcare team may recommend tests to find the extent of the cancer. The size of the cancer and whether it has spread is called the cancer's stage. The stage indicates how likely the cancer is to be cured. It helps the healthcare team to create a treatment plan.

Tests used to find the vaginal cancer stage include:

- Imaging tests. Imaging tests may include X-rays, CT, MRI or positron emission tomography, also called PET.

- Tiny cameras to see inside the body. Procedures that use tiny cameras to see inside the body may help determine whether cancer has spread to certain areas. A procedure to look inside the bladder is called cystoscopy. A procedure to look inside the rectum is called proctoscopy.

Information from these tests and procedures is used to assign the cancer a stage. The stages of vaginal cancer range from 1 to 4. The lowest number means that the cancer is only in the vagina. As the cancer becomes more advanced, the stages get higher. A stage 4 vaginal cancer may have grown to involve nearby organs or spread to other parts of the body.

Treatment

Treatment for most vaginal cancers often starts with radiation therapy and chemotherapy at the same time. For very small cancers, surgery might be the first treatment.

Your treatment options for vaginal cancer depend on several factors. This includes the type of vaginal cancer you have and its stage. You and your healthcare team work together to decide what treatments are best for you. Your team considers your goals for treatment and the side effects you're willing to accept.

Vaginal cancer treatment is usually coordinated by a doctor who specializes in treating cancers that affect the female reproductive system. This doctor is called a gynecologic oncologist.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy uses powerful energy beams to kill cancer cells. The energy comes from X-rays, protons or other sources. Radiation therapy procedures include:

- External radiation. External radiation also is called external beam radiation. It uses a large machine to direct beams of radiation at precise points on your body.

- Internal radiation. Internal radiation also is called brachytherapy. It involves putting radioactive devices in the vagina or near it. Types of devices include seeds, wires, cylinders or other materials. After a set amount of time, the devices may be removed. Internal radiation is often used after external radiation.

Most vaginal cancers are treated with a combination of radiation therapy and low-dose chemotherapy medicines. Chemotherapy is a treatment that uses strong medicines to kill cancer cells. Using a low dose of chemotherapy medicine during radiation treatments makes the radiation more effective.

Radiation also can be used after surgery to kill any cancer cells that might be left behind.

Surgery

Types of surgery that may be used to treat vaginal cancer include:

- Removal of the vagina. Vaginectomy is an operation to remove some or all of the vagina. It might be an option for small vaginal cancers that haven't grown beyond the vagina. It's typically used when the cancer is small and isn't near any important structures. If the cancer is growing near an important part, such as the tube that carries urine out of the body, surgery might not be an option.

- Removal of many of the pelvic organs. Pelvic exenteration is an operation to remove many of the pelvic organs. It might be used if cancer comes back or doesn't respond to other treatments. During pelvic exenteration, a surgeon may remove the bladder, ovaries, uterus, vagina and rectum. Openings are created in the abdomen to allow urine and waste to leave the body.

If your vagina is completely removed, you may choose to have surgery to make a new vagina. Surgeons use sections of skin or muscle from other areas of your body to form a new vagina.

A reconstructed vagina allows you to have vaginal intercourse. Sex may feel different after surgery. A reconstructed vagina lacks natural lubrication. It may lack feeling due to changes in the nerves.

Other options

If other treatments don't control your cancer, these treatments might be used:

- Chemotherapy. Chemotherapy uses strong medicines to kill cancer cells. Chemotherapy might be recommended if your cancer has spread to other parts of your body or if it comes back after other treatments.

- Immunotherapy. Immunotherapy is a treatment with medicine that helps your body's immune system to kill cancer cells. Your immune system fights off diseases by attacking germs and other cells that shouldn't be in your body. Cancer cells survive by hiding from the immune system. Immunotherapy helps the immune system cells find and kill the cancer cells. This might be an option if your cancer is advanced and other treatments haven't helped. Immunotherapy is often used to treat vaginal melanoma.

- Clinical trials. Clinical trials are experiments to test new treatment methods. While a clinical trial gives you a chance to try the latest treatment advances, a cure isn't guaranteed. If you're interested in trying a clinical trial, discuss it with your healthcare team.

Palliative care

Palliative care is a special type of healthcare that helps you feel better when you have a serious illness. If you have cancer, palliative care can help relieve pain and other symptoms. Palliative care is done by a team of healthcare professionals. This can include doctors, nurses and other specially trained professionals. Their goal is to improve the quality of life for you and your family.

Palliative care specialists work with you, your family and your care team to help you feel better. They provide an extra layer of support while you have cancer treatment. You can have palliative care at the same time as strong cancer treatments, such as surgery, chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

When palliative care is used along with all of the other appropriate treatments, people with cancer may feel better and live longer.

Coping and support

How you respond to your cancer diagnosis is unique. You might want to surround yourself with friends and family. Or you may ask for time alone to sort through your feelings. Until you find what works best for you, you might try to:

- Learn enough about your cancer to make decisions about your care. Write down the questions to ask at your next appointment. Ask a friend or family member to come to appointments with you to take notes. Ask your healthcare team for further sources of information. Knowing more can help make it easier to make decisions about your treatment.

-

Maintain intimacy with your partner. Vaginal cancer treatments are likely to cause side effects that make sexual intimacy more difficult. Find new ways of being intimate.

Spending quality time together and having meaningful conversations are ways to build your emotional intimacy. When you're ready for physical intimacy, take it slowly.

If sexual side effects of your cancer treatment are hurting your relationship with your partner, talk to your healthcare team.

-

Create a support network. Having friends and family supporting you can be valuable. You may find it helps to talk with someone about your emotions. Other sources of support include social workers and psychologists. Ask your healthcare team for recommendations if you feel like you need someone to talk with.

Talk with your pastor, rabbi or other spiritual leader. Consider joining a support group. Other people with cancer can offer a unique perspective and may better understand what you're going through. Contact the American Cancer Society for more information on support groups.

Preparing for an appointment

Start by making an appointment with your usual doctor, gynecologist or other healthcare professional if you have any symptoms that worry you. If you're found to have vaginal cancer, you may be referred to a doctor who specializes in cancers of the female reproductive system. This doctor is called a gynecologic oncologist.

It's a good idea to be prepared for your appointment. Here's some information to help you get ready.

What you can do

- Write down any symptoms you're experiencing, including any that may seem unrelated to the reason for which you scheduled the appointment.

- Write down key personal information, including any major stresses or recent life changes.

- Make a list of all medications, vitamins or supplements that you're taking.

- Ask a family member or friend to come with you. Sometimes it can be hard to remember all the information provided during an appointment. Someone who accompanies you may remember something that you missed or forgot.

- Write down questions to ask your healthcare professional.

Your time with your healthcare team is limited, so prepare a list of questions ahead of time to help make the most of your time together. List your questions from most important to least important in case time runs out. For vaginal cancer, some basic questions to ask include:

- What's the most likely cause of my symptoms?

- Are there any other possible causes for my symptoms?

- What kinds of tests do I need?

- What types of treatments are available? What kinds of side effects can I expect from each treatment? How will these treatments affect my sexuality?

- What do you think is the best course of action for me?

- What are the alternatives to the primary approach that you're suggesting?

- I have these other health conditions. How can I best manage them together?

- Are there any restrictions that I need to follow?

- Has my cancer spread? What stage is it?

- What's my prognosis?

- Should I see a specialist? What will that cost, and will my insurance cover it?

- Are there brochures or other printed material that I can take with me? What websites do you recommend?

In addition to the questions that you've prepared in advance, don't hesitate to ask questions as they occur to you during your appointment.

What to expect from your doctor

Be prepared to answer some basic questions about your health and your symptoms, such as:

- When did you begin experiencing symptoms?

- Have your symptoms been continuous or occasional?

- How severe are your symptoms?

- What, if anything, seems to improve your symptoms?

- What, if anything, appears to worsen your symptoms?

- Do you know if your mother took diethylstilbestrol, also called DES, during pregnancy?

- Do you have any personal history of cancer?

- Have you ever been told you have human papillomavirus, also called HPV?

- Have your Pap test results ever showed something concerning?

© 1998-2025 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use