Overview

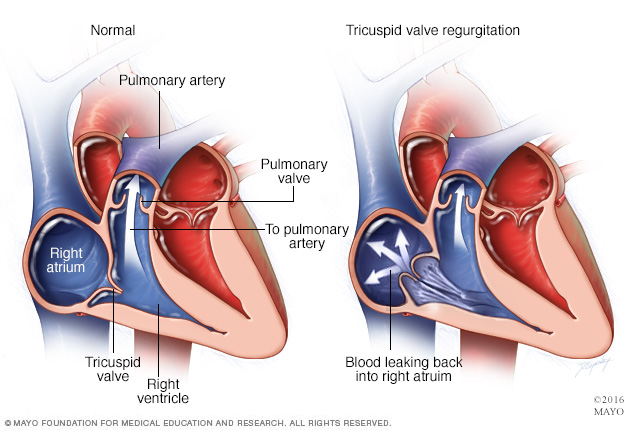

Tricuspid valve regurgitation is a type of heart valve disease. The valve between the two right heart chambers doesn't close as it should. Blood flows backward through the valve into the upper right chamber. If you have tricuspid valve regurgitation, less blood flows to the lungs. The heart has to work harder to pump blood.

The condition also may be called:

- Tricuspid regurgitation.

- Tricuspid insufficiency.

Some people are born with heart valve disease that leads to tricuspid regurgitation. This is called congenital heart valve disease. But tricuspid valve regurgitation also may occur later in life due to infections and other health conditions.

Mild tricuspid valve regurgitation may not cause symptoms or require treatment. If the condition is severe and causing symptoms, medicine or surgery may be needed.

Symptoms

Tricuspid valve regurgitation often doesn't cause symptoms until the condition is severe. It may be found when medical tests are done for another reason.

Symptoms of tricuspid valve regurgitation may include:

- Extreme tiredness.

- Shortness of breath with activity.

- Feelings of a rapid or pounding heartbeat.

- Pounding or pulsing feeling in the neck.

- Swelling in the belly, legs or neck veins.

When to see a doctor

Make an appointment for a health checkup if you get tired very easily or feel short of breath with activity. You may need to see a doctor trained in heart conditions, called a cardiologist.

Causes

To understand the causes of tricuspid valve regurgitation, it may help to know how the heart and heart valves typically work.

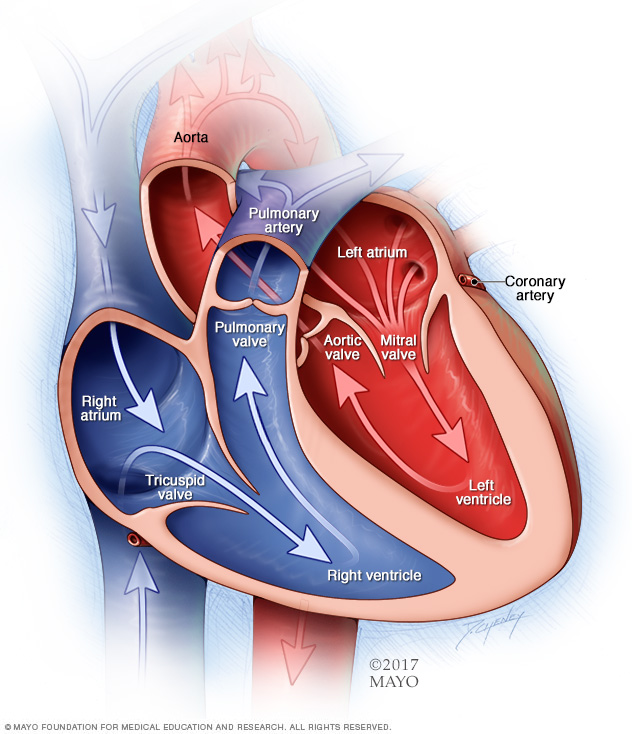

A typical heart has four chambers.

- The two upper chambers, called the atria, receive blood.

- The two lower chambers, called the ventricles, pump blood.

Four valves open and close to keep blood flowing in the correct direction. These heart valves are:

- Aortic valve.

- Mitral valve.

- Tricuspid valve.

- Pulmonary valve.

The tricuspid valve is between the heart's two right chambers. It has three thin flaps of tissue, called cusps or leaflets. These flaps open to let blood move from the upper right chamber to the lower right chamber. The valve flaps then close tightly so blood doesn't flow backward.

In tricuspid valve regurgitation, the tricuspid valve doesn't close tightly. So, blood leaks backward into the upper right heart chamber.

Causes of tricuspid valve regurgitation include:

- A heart problem you're born with, also called a congenital heart defect. Some congenital heart defects affect the shape of the tricuspid valve and how it works. Tricuspid valve regurgitation in children is usually caused by a rare heart problem present at birth called Ebstein anomaly. In this condition, the tricuspid valve does not form correctly. It also is lower than usual in the lower right heart chamber.

- Marfan syndrome. This condition is caused by changes in genes. It affects the fibers that support and anchor the organs and other structures in the body. It's occasionally associated with tricuspid valve regurgitation.

- Rheumatic fever. This complication of strep throat can cause permanent damage to the heart and heart valves. When that happens, it's called rheumatic heart valve disease.

- Infection of the lining of the heart and heart valves, also called infective endocarditis. This condition can damage the tricuspid valve. IV drug misuse increases the risk of infective endocarditis.

- Carcinoid syndrome. This condition occurs when a rare cancerous tumor releases certain chemicals into the bloodstream. It can lead to carcinoid heart disease, which damages heart valves, most commonly the tricuspid and pulmonary valves.

- Chest injury. An injury to the chest, such as from a car accident, may cause damage that leads to tricuspid valve regurgitation.

- Pacemaker or other heart device wires. Tricuspid valve regurgitation might happen if wires from a pacemaker or defibrillator cross the tricuspid valve.

- Heart biopsy, also called an endomyocardial biopsy. Heart valve damage can sometimes happen when a small amount of heart muscle tissue is removed for examination.

- Radiation therapy. Rarely, radiation therapy for cancer that is focused on the chest area can cause tricuspid valve regurgitation.

Risk factors

A risk factor is something that makes you more likely to get a sickness or other health condition.

Things that can increase the risk of tricuspid valve regurgitation are:

- An irregular heartbeat called atrial fibrillation (AFib).

- Being born with a heart problem, called a congenital heart defect.

- Damage to the heart muscle, including heart attack.

- Heart failure.

- High blood pressure in the lungs, also called pulmonary hypertension.

- Infections of the heart and heart valves.

- History of radiation therapy to the chest area.

- Use of some weight-loss drugs and medicines to treat migraines and mental health disorders.

Complications

Tricuspid valve regurgitation complications may depend on how severe the condition is. Possible complications of tricuspid regurgitation include:

- An irregular and often rapid heartbeat, called atrial fibrillation (AFib). Some people with severe tricuspid valve regurgitation also have this common heart rhythm disorder. AFib has been linked to an increased risk of blood clots and stroke.

- Heart failure. In severe tricuspid valve regurgitation, the heart has to work harder to pump enough blood to the body. The extra effort causes the lower right heart chamber to get bigger. Untreated, the heart muscle becomes weak. This can cause heart failure.

Diagnosis

Tricuspid valve regurgitation can occur silently. It may be found when imaging tests of the heart are done for other reasons.

To diagnose tricuspid valve regurgitation, a healthcare professional examines you and asks questions about your symptoms and medical history. The care professional listens to your heart using a device called a stethoscope. A whooshing sound called a heart murmur may be heard.

Tests

To learn if you have tricuspid valve regurgitation, tests are done to check your heart and heart valves. The tests can show how severe any valve disease is and help learn the cause.

Tests to diagnose tricuspid valve regurgitation may include:

-

Echocardiogram. This is the main test for diagnosing tricuspid valve regurgitation. It uses sound waves to create pictures of the beating heart. It shows how blood flows through the heart and the heart valves, including the tricuspid valve.

There are different types of echocardiograms. A standard echocardiogram is called a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE). It creates pictures of the heart from outside the body. Sometimes, a more-detailed echocardiogram is needed to better see the tricuspid valve. This test is called a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE). It creates pictures of the heart from inside the body. The type of echocardiogram you have depends on the reason for the test and your overall health.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG). This quick test records the electrical signals in the heart. It shows how the heart is beating. Sensors, called electrodes, stick to the chest and sometimes the legs. Wires connect the sensors to a computer, which displays or prints results.

- Chest X-ray. A chest X-ray shows the condition of the heart and lungs.

- Cardiac MRI. This test uses magnetic fields and radio waves to create detailed pictures of the heart. Cardiac MRI may help show the severity of tricuspid valve regurgitation. The test also gives details about the lower right heart chamber.

- Cardiac catheterization. This test isn't often used to diagnose tricuspid valve disease. But it can be helpful if other tests haven't diagnosed the cause of the condition. A doctor guides a thin, flexible tube called a catheter through a blood vessel in the arm or groin. It's moved to an artery in the heart. Dye flows through the tube. This makes the heart arteries show up more clearly on X-rays taken during the test. Pressures in the heart also can be measured during this test.

Staging

After testing confirms a diagnosis of tricuspid or other heart valve disease, your healthcare team may tell you the stage of disease. Staging helps determine the most appropriate treatment.

The stage of heart valve disease depends on many things, including symptoms, disease severity, the structure of the valve or valves, and blood flow through the heart and lungs.

Heart valve disease is staged into four basic groups:

- Stage A: At risk. Risk factors for heart valve disease are present.

- Stage B: Progressive. Valve disease is mild or moderate. There are no heart valve symptoms.

- Stage C: Asymptomatic severe. There are no heart valve symptoms, but the valve disease is severe.

- Stage D: Symptomatic severe. Heart valve disease is severe and is causing symptoms.

Treatment

Treatment for tricuspid valve regurgitation depends on the cause and how severe it is. The goals of treatment are to:

- Help the heart work better.

- Reduce symptoms.

- Improve quality of life.

- Prevent complications.

Tricuspid regurgitation treatment may include:

- Medicines.

- A heart procedure.

- Surgery to repair or replace the heart valve.

The exact treatment depends on your symptoms and how severe the valve disease is. Some people with mild tricuspid valve regurgitation only need regular health checkups. Your healthcare team tells you how often you need appointments.

Medications

Your healthcare professional may suggest medicines to control symptoms of tricuspid valve regurgitation. Medicines also may be used to treat the cause.

Some medicines used for tricuspid valve regurgitation are:

- Diuretics. Often called water pills, these medicines make you urinate more often. This helps prevent fluid buildup in the body.

- Potassium-sparing diuretics. Also called aldosterone antagonists, these medicines may help some people with heart failure live longer.

- Other medicines to treat or control heart failure.

- Medicines to control irregular heartbeats. Some people with tricuspid regurgitation have a type of irregular heartbeat called atrial fibrillation (AFib).

Therapies

Supplemental oxygen may be given to those who have pulmonary hypotension with tricuspid regurgitation.

Surgery or other procedures

Surgery may be needed to repair or replace a diseased or damaged tricuspid valve.

Tricuspid valve repair or replacement may be done as open-heart surgery or as a minimally invasive heart surgery. Sometimes, tricuspid valve disease may be treated with a catheter-based procedure. The treatment can help improve blood flow and reduce symptoms of heart valve disease.

You may need tricuspid valve repair or replacement surgery if:

- The valve disease is severe and you have symptoms such as shortness of breath.

- Your heart is growing larger or weaker, even if you don't have symptoms of tricuspid regurgitation.

- You have tricuspid valve regurgitation and need heart surgery for another condition, such as mitral valve disease.

Types of heart valve surgery to treat tricuspid regurgitation include:

-

Tricuspid valve repair. Surgeons recommend valve repair when possible. It saves the heart valve. It also may reduce the need for long-term use of blood thinners.

Tricuspid valve repair is traditionally done as an open-heart surgery. A long cut is made in the center of the chest. A surgeon may patch holes or tears in the valve, or separate or reconnect valve flaps. Sometimes the surgeon removes or reshapes tissue to help the tricuspid valve close more tightly. The cords of tissue that support the valve also may be replaced.

If tricuspid regurgitation is caused by Ebstein anomaly, heart surgeons may do a type of valve repair called the cone procedure. During the cone procedure, the surgeon separates the valve flaps that close off the tricuspid valve from the underlying heart muscle. The flaps are then rotated and reattached.

-

Tricuspid valve replacement. If the tricuspid valve can't be repaired, surgery may be needed to replace the valve. Tricuspid valve replacement surgery may be done as open-heart surgery or minimally invasive surgery.

During tricuspid valve replacement, a surgeon removes the damaged or diseased valve. The valve is replaced with a mechanical valve or a valve made from cow, pig or human heart tissue. A tissue valve is called a biological valve.

If you have a mechanical valve, you need to take blood thinners for the rest of your life to prevent blood clots. Biological tissue valves don't require lifelong blood thinners. But they can wear down over time and may need to be replaced. Together, you and your care team discuss the risks and benefits of each type of valve to determine the best one for you.

- Valve-in-valve replacement. If you have a biological tissue tricuspid valve that's no longer working, a catheter procedure may be done instead of open-heart surgery to replace the valve. The doctor inserts a thin, hollow tube called a catheter into a blood vessel and guides it to the tricuspid valve. The replacement valve goes through the catheter and into the existing biological valve.

After tricuspid repair or replacement, regular health checkups are needed to make sure the heart is working as it should.

Pregnancy

Careful and regular checkups are needed for those who have tricuspid valve disease during pregnancy. If you have tricuspid regurgitation, you may be told not to get pregnant to reduce the risk of complications, including heart failure.

Lifestyle and home remedies

If you have tricuspid regurgitation or any type of heart disease, your healthcare team may suggest making lifestyle changes. Try these steps:

- Eat a heart-healthy diet. Eat a variety of fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins. Avoid saturated fats and trans fats, sugar, and refined grains. Do not add salt to foods. If you have heart failure, your care team may tell you to limit fluids and salt.

- Don't smoke or use tobacco. If you smoke or chew tobacco, quit. Smoking is a major risk factor for heart disease. Quitting is the best way to reduce the risk. If you need help quitting, talk to a healthcare professional.

- Get regular exercise. Exercise can help improve heart health. As a general goal, aim for at least 30 minutes of moderate physical activity every day. Talk to your healthcare team before starting a new exercise routine.

- Maintain a healthy weight. Being overweight is a risk factor for heart disease. Talk with your care team to set realistic goals for weight.

- Practice good sleep habits. Poor sleep may increase the risk of heart disease. Adults should aim to get 7 to 9 hours of sleep daily. Go to bed and wake at the same time every day, including on weekends. If you have trouble sleeping, talk to your healthcare team.

- Control blood pressure. Uncontrolled high blood pressure increases the risk of serious health problems.

- Get a cholesterol test. Ask your care team how often you need a cholesterol test.

- Manage diabetes. If you have diabetes, tight blood sugar control can help keep your heart healthy.

If you had your tricuspid valve replaced, ask your care team if you need to take antibiotics before some types of dental work, such as gum surgery. Antibiotics are sometimes recommended for some people with heart valve replacements. The antibiotics prevent germs from getting into the lining of the heart, a condition called infective endocarditis.

Coping and support

If you have heart valve disease, such as tricuspid valve regurgitation, here are some ways to help you manage your condition and thrive.

- Take medicines as directed. Tell your healthcare team about all the medicines you take. Include those bought without a prescription.

- Get support. Connecting with friends and family or a support group is a good way to reduce stress. You may find that talking about your concerns with others in similar situations can help.

- Manage stress. Find ways to help reduce emotional stress. Getting more exercise, practicing mindfulness, and connecting with others in support groups are some ways to reduce and manage stress. If you have anxiety or depression, talk to your healthcare team about strategies to help.

- Stay active. It's a good idea to stay physically active. Your healthcare team may give you recommendations about how much and what type of exercise is appropriate for you.

Preparing for an appointment

If a healthcare professional thinks you might have tricuspid valve regurgitation, you are usually sent to a doctor trained in heart diseases. This type of doctor is called a cardiologist. If you were born with a heart problem, you may see a type of heart doctor called a congenital cardiologist.

Here's some information to help you get ready, and what to expect from your healthcare provider.

What you can do

- Be aware of any pre-appointment restrictions. When you make the appointment, ask if there's anything you need to do in advance. For example, you may be told not to eat or drink for a short period before a cholesterol test.

- Write down your symptoms, including any that seem unrelated to tricuspid valve regurgitation.

- Write down important personal information, including a family history of heart valve disease, and any major stresses or recent life changes.

- Make a list of all the medicines, vitamins and supplements that you take. Include those bought without a prescription. Also include the dosages.

- Take someone with you, if possible. Someone who goes with you can help you remember information you're given.

- Write down questions to ask the healthcare team.

Your time with the healthcare professional is limited. Preparing a list of questions can help you make the most of your time together. For tricuspid valve regurgitation, some basic questions to ask your care team include:

- What's the most likely cause of my symptoms?

- What tests do I need? Do these tests require any special preparation?

- I feel OK. Do I even need treatment?

- What tests do I need?

- What's the best treatment?

- What are the options to the main treatment that you're suggesting?

- I have other health conditions. How can I best manage them together?

- Are there any activity, sports or diet restrictions I need to follow?

- Should I see a specialist?

- If I need heart valve surgery, which surgeon do you recommend?

- Are there any brochures or other printed material that I can take home with me?

- Can you recommend any websites for more information on my condition?

Don't hesitate to ask other questions.

What to expect from your doctor

Your healthcare team is likely to ask you a number of questions. Being ready to answer them may save time to go over any questions or concerns you want to spend more time on. Your care team may ask:

- When did you first notice symptoms?

- Do you always have symptoms or do they come and go?

- How severe are your symptoms?

- What, if anything, makes your symptoms better?

- What, if anything, makes your symptoms worse?

© 1998-2025 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use