Overview

Neuroblastoma is a cancer that starts in cells called neuroblasts. Neuroblasts are immature nerve cells. They are found in several areas of the body.

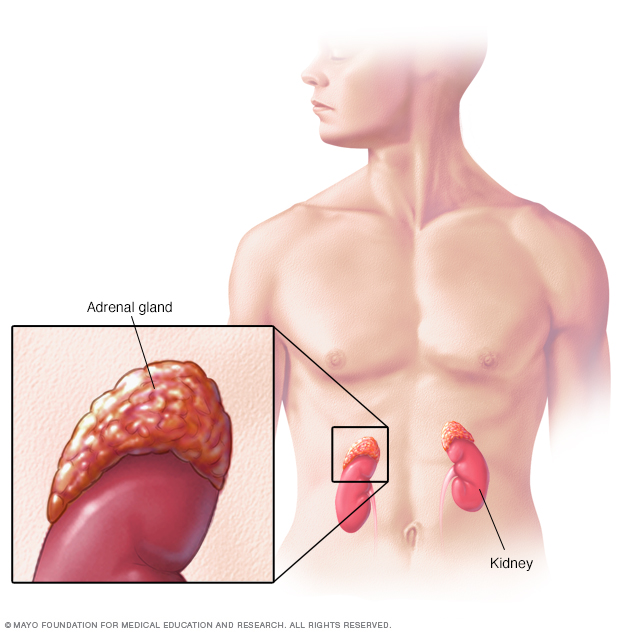

Neuroblastoma most often starts in the neuroblasts in the adrenal glands. The adrenal glands are located on top of each kidney. The glands make hormones that control important functions in the body. Other parts of the body that have neuroblasts and can get neuroblastoma include the spine, belly, chest and neck.

Neuroblastoma usually affects children age 5 or younger. Symptoms vary, depending on where it occurs in the body.

Some forms of neuroblastoma may go away on their own. Other forms of neuroblastoma need treatment. Treatments include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy and bone marrow transplant. Your child's healthcare team will select the neuroblastoma treatments that are best for your child.

Symptoms

Signs and symptoms of neuroblastoma may vary depending on what part of the body is affected. This cancer starts in immature nerve cells called neuroblasts. Neuroblasts are found in several areas of the body.

Neuroblastoma in the belly may cause symptoms such as:

- Belly pain.

- A lump under the skin that typically isn't tender when touched.

- Diarrhea or constipation.

Neuroblastoma in the chest may cause symptoms such as:

- Wheezing.

- Difficulty breathing.

- Changes to the eyes, including drooping eyelids and pupils that are different sizes.

Other symptoms that may indicate neuroblastoma include:

- Lumps of tissue under the skin.

- Eyeballs that seem to stick out from the sockets.

- Dark circles around the eyes that look like bruises.

- Back pain.

- Fever.

- Losing weight without trying.

- Bone pain.

When to see a doctor

Contact your child's healthcare professional if your child has any symptoms that worry you. Mention any changes in your child's behavior, habits or appearance.

Causes

It's not clear what causes neuroblastoma. This cancer starts in immature nerve cells called neuroblasts. Neuroblasts are found in several areas of the body.

Neuroblastoma starts when neuroblasts develop changes in their DNA. A cell's DNA holds the instructions that tell the cell what to do. In healthy cells, the DNA gives instructions to grow and multiply at a set rate. The instructions tell the cells to die at a set time. In cancer cells, the DNA changes give different instructions. The changes tell the cancer cells to grow and multiply quickly. Cancer cells can keep living when healthy cells would die. This causes too many cells.

The cancer cells might form a mass called a tumor. The tumor can grow to invade and destroy healthy body tissue. In time, cancer cells can break away and spread to other parts of the body. When cancer spreads, it's called metastatic cancer.

Risk factors

The risk of neuroblastoma is higher in children. This cancer happens mostly in children age 5 and younger.

Children with a family history of neuroblastoma may be more likely to develop the disease. Yet, healthcare professionals think only a small number of neuroblastomas are inherited.

There are no known ways to prevent neuroblastoma.

Complications

Complications of neuroblastoma may include:

- Spread of the cancer. With time, the cancer cells may spread to other parts of the body. Neuroblastoma cells most often spread to the lymph nodes, bone marrow, liver, skin and bones. When cancer spreads, it's called metastatic cancer.

- Pressure on the spinal cord. A neuroblastoma may grow and press on the spinal cord, causing spinal cord compression. Spinal cord compression may cause pain and paralysis.

- Symptoms caused by cancer secretions. Neuroblastoma cells may secrete chemicals that irritate other tissues. The irritated tissues can cause symptoms called paraneoplastic syndromes. Symptoms of paraneoplastic syndromes may include rapid eye movements and difficulty with coordination. Other symptoms include abdominal swelling and diarrhea.

Diagnosis

A neuroblastoma diagnosis might start with a physical exam. Other tests and procedures include imaging tests and removing some tissue for testing. Your child's healthcare team may use a variety of tests and procedures to diagnose this cancer.

Physical exam

A healthcare professional may examine your child to check for signs of neuroblastoma. The healthcare professional may ask you questions about your child's symptoms and health history.

Urine and blood tests

A healthcare professional might test your child's urine and blood. The results can help the healthcare professional better understand your child's condition. Urine tests might look for high levels of chemicals made by neuroblastoma cells. For example, neuroblastoma can produce chemicals called catecholamines. These might be detected by a urine test.

Imaging tests

Imaging tests make pictures of the body. They may help your child's healthcare team find the location of neuroblastoma and look for signs that it may have spread.

Imaging tests for neuroblastoma may include:

- X-ray.

- Ultrasound.

- Computerized tomography scan, also called CT scan.

- Magnetic resonance imaging, also called MRI.

- Metaiodobenzylguanidine scan, also called MIBG scan.

Not everyone needs each test. The healthcare team will decide which tests are needed based on your child's condition.

Biopsy

A biopsy is a procedure to remove a sample of tissue for testing in a lab. To get the sample, a healthcare professional might put a hollow needle through the skin and into the cancer. The health professional uses the needle to draw out some cells for testing. Sometimes a surgeon removes the tissue sample during surgery.

In the lab, tests can check the tissue for signs of cancer. Other tests might look for changes in the DNA inside the cancer cells. Results from these tests may help your child's healthcare team make a treatment plan.

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy are procedures that involve collecting cells from the bone marrow. The cells are sent for testing. These procedures are used to check if neuroblastoma has spread to the bone marrow.

Bone marrow is the soft matter inside bones where blood cells are made. Bone marrow has a solid part and a liquid part. In a bone marrow aspiration, a needle is used to draw a sample of the fluid. In a bone marrow biopsy, a needle is used to collect a small amount of the solid tissue. The samples are typically taken from the hip bone.

Neuroblastoma stages

The healthcare team uses the results from these tests to give the neuroblastoma a stage. The stage tells the healthcare team about the prognosis and helps the team create a treatment plan.

The stages of neuroblastoma are:

- L1. This stage means the neuroblastoma is growing in one area. The caner doesn't involve any structures that would make it hard to remove the cancer completely with surgery.

- L2. This stage means the neuroblastoma is growing in one area. However, the cancer involves structures that might make it hard to remove all the cancer with surgery.

- M. This stage means the neuroblastoma has spread to other parts of the body.

- MS. This stage applies to children younger than 18 months. It means the neuroblastoma has spread to the skin, liver or bone marrow.

Treatment

Treatments for neuroblastoma include surgery, radiation therapy, and medicines, such as chemotherapy and others. Healthcare teams consider many things when creating a treatment plan. These include the child's age, the stage of the cancer, the kinds of cells involved in the cancer and the DNA changes inside the cancer cells.

The healthcare team uses this information to say whether the neuroblastoma is low risk, intermediate risk or high risk. Neuroblastoma that is low risk or intermediate risk has a good chance for cure. High risk neuroblastoma can be more difficult to cure, so stronger treatments might be needed. What treatment or combination of treatments your child receives for neuroblastoma depends on the risk category.

Surgery

During surgery for neuroblastoma, surgeons use cutting tools to remove the cancer cells. In children with low-risk neuroblastoma, surgery to remove the cancer may be the only treatment needed.

Whether the cancer can be removed completely depends on its location and size. Cancers that are attached to nearby vital organs may be too risky to remove.

In intermediate-risk and high-risk neuroblastoma, surgeons may try to remove as much of the cancer as possible. Other treatments, such as chemotherapy and radiation therapy, may then be used to kill remaining cancer cells.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy treats cancer with strong medicines. Many chemotherapy medicines exist. Most chemotherapy medicines are given through a vein. Some come in pill form.

Children with intermediate-risk neuroblastoma often receive a combination of chemotherapy medicines before surgery. This improves the chances that the entire cancer can be removed.

Children with high-risk neuroblastoma often receive high doses of chemotherapy medicines to shrink the cancer. Chemotherapy also helps kill any cancer cells that have spread to other parts in the body. Chemotherapy often is used before surgery and before bone marrow transplant.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy treats cancer with powerful energy beams. The energy can come from X-rays, protons or other sources.

Children with high-risk neuroblastoma may receive radiation therapy after chemotherapy and surgery. The radiation can help lower the risk that the cancer will come back.

Bone marrow transplant

A bone marrow transplant, also called a bone marrow stem cell transplant, involves putting healthy bone marrow stem cells into the body. These cells replace cells hurt by chemotherapy and other treatments.

A bone marrow transplant might be an option for children with high-risk neuroblastoma. A bone marrow transplant for neuroblastoma uses the child's own blood stem cells. This kind of transplant is called an autologous stem cell transplant.

Before the transplant, a procedure is done to filter and collect blood stem cells from the child's blood. The stem cells are stored for later use. Next, the child receives high doses of chemotherapy to kill any remaining cancer cells. Then the blood stem cells are put back into the child's body. The transplanted cells can form new, healthy blood cells.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a treatment with medicine that helps the body's immune system kill cancer cells. The immune system fights off diseases by attacking germs and other cells that shouldn't be in the body. Cancer cells survive by hiding from the immune system. Immunotherapy helps the immune system cells find and kill the cancer cells.

Immunotherapy is sometimes used with chemotherapy for high-risk neuroblastoma.

Coping and support

When your child is diagnosed with cancer, it's common to feel a range of emotions. Some parents say they had feelings such as shock, disbelief, guilt and anger. At the time you might be feeling these strong feelings, you also may need to make decisions about your child's treatment. This can feel overwhelming. Here are some ideas to help with coping.

Gather all the information you need

Find out enough about neuroblastoma to feel comfortable making decisions about your child's care. Talk with your child's healthcare team. Keep a list of questions to ask at the next appointment. Ask your child's healthcare team to recommend good sources of information. In the United States, the National Cancer Institute and the American Cancer Society are good organizations to go to for more information.

Organize a support network

Friends and family can provide both emotional and practical support as your child goes through treatment. Your friends and family will likely ask you what they can do to help. Take them up on their offers. Loved ones can go with your child to healthcare visits or sit by your child's bedside in the hospital when you can't be there. When you're with your child, your friends and family can help out by spending time with your other children or helping around your home.

Take advantage of resources for children with cancer

Seek out special resources for families of kids with cancer. Ask your clinic's social workers about what's available. Support groups for parents and siblings put you in touch with people who understand what you're feeling. Your family may be eligible for summer camps, temporary housing and other support.

Maintain your usual routines as much as possible

Small children can't understand what's happening to them as they undergo cancer treatment. To help your child cope, try to keep your usual routines as much as possible. Try to arrange appointments so that your child can have a set nap time each day. Have routine mealtimes. Allow time for play when your child feels up to it. If your child must spend time in the hospital, bring items from home that help your child feel more comfortable.

Ask your healthcare team about other ways to comfort your child through treatment. Some hospitals have recreation therapists or child life workers who can give you more-specific ways to help your child cope.

Preparing for an appointment

Make an appointment with your family healthcare professional if your child has any symptoms that worry you.

Because appointments can be brief it's a good idea to be prepared. Here's some information to help you get ready, and what to expect.

What you can do

- Be aware of any preappointment restrictions. At the time you make the appointment, be sure to ask if there's anything you need to do in advance, such as change your child's diet.

- Write down any symptoms your child is experiencing, including any that may seem unrelated to the reason for which you scheduled the appointment.

- Write down key personal information, including any major stresses or recent life changes.

- Make a list of all medicines, vitamins or supplements your child is taking and the doses.

- Consider taking a family member or friend along. Sometimes it can be hard to remember all the information provided during an appointment. Someone who comes with you may remember something that you missed or forgot.

- Write down questions to ask your child's healthcare team.

Your time with your child's healthcare team may be limited, so preparing a list of questions can help you make the most of your time together. List your questions from most important to least important in case time runs out. For neuroblastoma, some basic questions to ask include:

- What may be causing my child's symptoms or condition?

- What kinds of tests does my child need?

- What is the best course of action?

- What are the alternatives to the approach that you're suggesting?

- My child has these other health conditions. How can they best be managed together?

- Are there any restrictions that my child needs to follow?

- Should my child see a specialist?

- Where can I find more information?

In addition to the questions that you've prepared, don't hesitate to ask other questions during your appointment.

What to expect from your child's doctor

Your child's healthcare team is likely to ask you questions, such as:

- When did your child begin experiencing symptoms?

- How have your child's symptoms changed over time?

- What, if anything, seems to improve your child's symptoms?

- What, if anything, appears to worsen your child's symptoms?

© 1998-2025 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use