Overview

Iritis (i-RYE-tis) is swelling and irritation (inflammation) in the colored ring around your eye's pupil (iris). Another name for iritis is anterior uveitis.

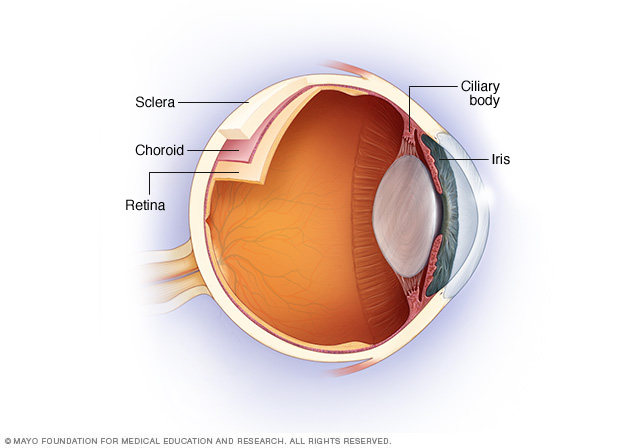

The uvea is the middle layer of the eye between the retina and the white part of the eye. The iris is located in the front portion (anterior) of the uvea.

Iritis is the most common type of uveitis. Uveitis is inflammation of part of or all of the uvea. The cause is often unknown. It can result from an underlying condition or genetic factor.

If untreated, iritis could lead to glaucoma or vision loss. See your doctor as soon as possible if you have symptoms of iritis.

Symptoms

Iritis can occur in one or both eyes. It usually develops suddenly, and can last up to three months.

Signs and symptoms of iritis include:

- Eye redness

- Discomfort or achiness in the affected eye

- Sensitivity to light

- Decreased vision

Iritis that develops suddenly, over hours or days, is known as acute iritis. Symptoms that develop gradually or last longer than three months indicate chronic iritis.

When to see a doctor

See an eye specialist (ophthalmologist) as soon as possible if you have symptoms of iritis. Prompt treatment helps prevent serious complications. If you have eye pain and vision problems with other signs and symptoms, you might need urgent medical care.

Causes

Often, the cause of iritis can't be determined. In some cases, iritis can be linked to eye trauma, genetic factors or certain diseases. Causes of iritis include:

- Injury to the eye. Blunt force trauma, a penetrating injury, or a burn from a chemical or fire can cause acute iritis.

-

Infections. Viral infections on your face, such as cold sores and shingles caused by herpes viruses, can cause iritis.

Infectious diseases from other viruses and bacteria can also be linked to uveitis. For instance, they may include toxoplasmosis, an infection most often caused by a parasite in uncooked food; histoplasmosis, a lung infection that occurs when you inhale spores of fungus; tuberculosis, which happens when bacteria enters the lungs; and syphilis, which is caused by the spread of bacteria through sexual contact.

- Genetic predisposition. People who develop certain autoimmune diseases because of a gene alteration that affects their immune systems might also develop acute iritis. Diseases include a type of arthritis called ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease and psoriatic arthritis.

- Behcet's disease. An uncommon cause of acute iritis in Western countries, this condition is also characterized by joint problems, mouth sores and genital sores.

- Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Chronic iritis can develop in children with this condition.

- Sarcoidosis. This autoimmune disease involves the growth of collections of inflammatory cells in areas of your body, including your eyes.

- Certain medications. Some drugs, such as the antibiotic rifabutin (Mycobutin) and the antiviral medication cidofovir, that are used to treat HIV infections can be a rare cause of iritis. Rarely, bisphosphonates, used to treat osteoporosis, can cause uveitis. Stopping these medications usually stops the iritis symptoms.

Risk factors

Your risk of developing iritis increases if you:

- Have a specific genetic alteration. People with a specific change in a gene that's essential for healthy immune system function are more likely to develop iritis. This change is labeled HLA-B27.

- Develop a sexually transmitted infection. Certain infections, such as syphilis or HIV/AIDS, are linked with a significant risk of iritis.

- Have a weakened immune system or an autoimmune disorder. This includes conditions such as ankylosing spondylitis and reactive arthritis.

- Smoke tobacco. Studies have shown that smoking contributes to your risk.

Complications

If not treated properly, iritis could lead to:

- Cataracts. Development of a clouding of the lens of your eye (cataract) is a possible complication, especially if you've had a long period of inflammation.

- An irregular pupil. Scar tissue can cause the iris to stick to the underlying lens or the cornea, making the pupil irregular in shape and the iris sluggish in its reaction to light.

- Glaucoma. Recurrent iritis can result in glaucoma, a serious eye condition characterized by increased pressure inside the eye and possible vision loss.

- Calcium deposits on the cornea. This causes degeneration of your cornea and could decrease your vision.

- Swelling within the retina. Swelling and fluid-filled cysts that develop in the retina at the back of the eye can blur or decrease your central vision.

Diagnosis

Your eye doctor will conduct a complete eye exam, including:

- External examination. Your doctor might use a penlight to look at your pupils, observe the pattern of redness in one or both eyes, and check for signs of discharge.

- Visual acuity. Your doctor tests how sharp your vision is using an eye chart and other standard tests.

- Slit-lamp examination. Using a special microscope with a light on it, your doctor views the inside of your eye looking for signs of iritis. Dilating your pupil with eyedrops enables your doctor to see the inside of your eye better.

If your eye doctor suspects that a disease or condition is causing your iritis, he or she may work with your primary care doctor to pinpoint the underlying cause. In that case, further testing might include blood tests or X-rays to identify or rule out specific causes.

Treatment

Iritis treatment is designed to preserve vision and relieve pain and inflammation. For iritis associated with an underlying condition, treating that condition also is necessary.

Most often, treatment for iritis involves:

- Steroid eyedrops. Glucocorticoid medications, given as eyedrops, reduce inflammation.

- Dilating eyedrops. Eyedrops used to dilate your pupil can reduce the pain of iritis. Dilating eyedrops also protect you from developing complications that interfere with your pupil's function.

If your symptoms don't clear up, or seem to worsen, your eye doctor might prescribe oral medications that include steroids or other anti-inflammatory agents, depending on your overall condition.

Preparing for an appointment

Make an appointment with a doctor who specializes in eye care — an optometrist or an ophthalmologist — who can evaluate iritis and perform a complete eye exam.

Here's some information to help you get ready for your appointment.

What you can do

Make a list of:

- Your symptoms, including any that may seem unrelated to your vision problem and when they began

- All medications, vitamins or supplements you take, including doses

- Key personal information, including recent trauma or injury and your family medical history, including whether any family member has an autoimmune disorder

- Questions to ask your eye doctor

Take a family member or friend to your appointment, if possible, to help you remember information you're given. Also, having your pupils dilated for the eye exam will affect your vision for a time afterward, so it might be helpful to have someone drive you home.

For iritis, some questions to ask your doctor include:

- Can iritis permanently affect my vision?

- Do I need to come back for follow-up exams? When?

- What should I do if my symptoms don't go away or seem to worsen?

- I have other health conditions. How can I best manage them together?

- Do you have brochures or other printed material I can have? What websites do you recommend?

What to expect from your eye doctor

Your doctor is likely to ask you several questions, such as:

- Do you have symptoms in one or both eyes?

- Do you feel pain in your eye after touching your eyelid?

- Do you have headaches?

- Does bright light worsen your eye pain?

- Is your vision blurred?

- Do you have symptoms of arthritis, such as joint pain?

- Do you have sores in your mouth or on your genitals?

- Have you been diagnosed with iritis before?

- Have you been diagnosed with other eye conditions?

- How are you feeling overall?

© 1998-2025 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use