Overview

Gastroparesis is a condition in which the muscles in the stomach don't move food as they should for it to be digested.

Most often, muscles contract to send food through the digestive tract. But with gastroparesis, the stomach's movement, called motility, slows or doesn't work at all. This keeps the stomach from emptying well.

Often, the cause of gastroparesis is not known. Sometimes it's linked to diabetes. And some people get gastroparesis after surgery or after a viral illness.

Certain medicines, such as opioid pain relievers, some antidepressants, and medicines for high blood pressure, weight loss and allergies can slow stomach emptying. The symptoms can be like those of gastroparesis. For people who already have gastroparesis, these medicines may make the condition worse.

Gastroparesis affects digestion. It can cause nausea, vomiting and belly pain. It also can cause problems with blood sugar levels and nutrition. There's no cure for gastroparesis. But medicines and changes to diet can give some relief.

Symptoms

Symptoms of gastroparesis include:

- Vomiting.

- Nausea.

- Belly bloating.

- Belly pain.

- Feeling full after eating just a few bites and long after eating a meal.

- Vomiting undigested food eaten a few hours earlier.

- Acid reflux.

- Changes in blood sugar levels.

- Not wanting to eat.

- Weight loss and not getting enough nutrients, called malnutrition.

Many people with gastroparesis don't notice any symptoms.

When to see a doctor

Make an appointment with your healthcare professional if you have symptoms that worry you.

Causes

It's not always clear what leads to gastroparesis. But sometimes damage to a nerve that controls the stomach muscles can cause it. This nerve is called the vagus nerve.

The vagus nerve helps manage what happens in the digestive tract. This includes telling the muscles in the stomach to contract and push food into the small intestine. A damaged vagus nerve can't send signals to the stomach muscles as it should. This may cause food to stay in the stomach longer.

Conditions such as diabetes or surgery to the stomach or small intestine can damage the vagus nerve and its branches.

Risk factors

Factors that can raise the risk of gastroparesis include:

- Diabetes.

- Surgery on the stomach area or on the tube that connects the throat to the stomach, called the esophagus.

- Infection with a virus.

- Certain cancers and cancer treatments, such as radiation therapy to the chest or stomach.

- Certain medicines that slow the rate of stomach emptying, such as opioid pain medicines.

- A condition that causes the skin to harden and tighten, called scleroderma.

- Nervous system diseases, such as migraine, Parkinson's disease or multiple sclerosis.

- Underactive thyroid, also called hypothyroidism.

People assigned female at birth are more likely to get gastroparesis than are people assigned male at birth.

Complications

Gastroparesis can cause several complications, such as:

- Loss of body fluids, called dehydration. Repeated vomiting can cause dehydration.

- Malnutrition. Not wanting to eat can mean you don't take in enough calories. Or your body may not be able to take in enough nutrients due to vomiting.

- Food that doesn't digest that hardens and stays in the stomach. This food can harden into a solid mass called a bezoar. Bezoars can cause nausea and vomiting. They may be life-threatening if they keep food from passing into the small intestine.

- Blood sugar changes. Gastroparesis doesn't cause diabetes. But the changes in the rate and amount of food passing into the small bowel can cause sudden changes in blood sugar levels. These blood sugar changes can make diabetes worse. In turn, poor control of blood sugar levels makes gastroparesis worse.

- Lower quality of life. Symptoms can make it hard to work and keep up with daily activities.

Diagnosis

Several tests help diagnose gastroparesis and rule out other conditions that may cause symptoms like those of gastroparesis. Tests may include:

Gastric emptying tests

To see how fast your stomach empties, you may have one or more of these tests:

-

Scintigraphy. This is the main test used to diagnose gastroparesis. It involves eating a light meal, such as eggs and toast, that has a small amount of radioactive material in it. A scanner follows the movement of the radioactive material. The scanner goes over the belly to show the rate at which food leaves the stomach.

This test takes about four hours. You'll need to stop taking any medicines that could slow gastric emptying. Ask your healthcare professional what not to take.

-

Breath tests. For breath tests, you consume a solid or liquid food that has a substance that your body absorbs. In time, the substance shows up in your breath.

Your healthcare team collects samples of your breath over a few hours to measure the amount of the substance in your breath. The amount of substance in your breath shows how fast your stomach empties.

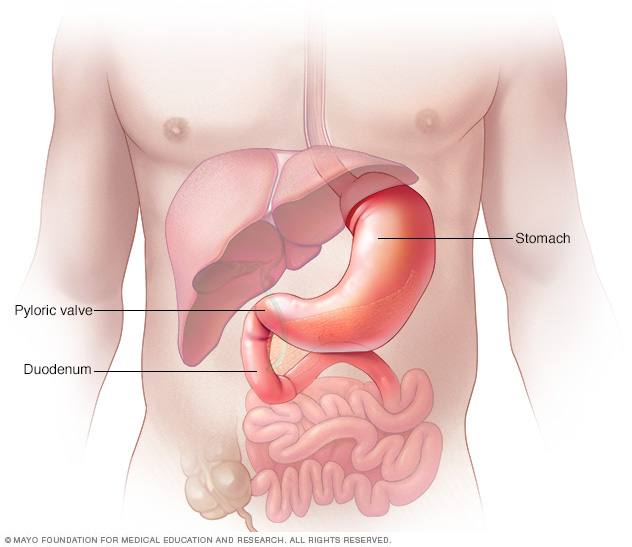

Upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy

This procedure is used to see the tube that connects the throat to the stomach, called the esophagus, the stomach and beginning of the small intestine, called the duodenum. It uses a tiny camera on the end of a long, flexible tube.

This test also can diagnose other conditions that can have symptoms like those of gastroparesis. Examples are peptic ulcer disease and pyloric stenosis.

Ultrasound

This test uses high-frequency sound waves to make images of structures within the body. Ultrasound can help diagnose whether problems with the gallbladder or kidneys could be causing symptoms.

Treatment

Treating gastroparesis begins with finding and treating the condition that's causing it. If diabetes is causing your gastroparesis, your healthcare professional can work with you to help you control your blood sugar levels.

Changes to your diet

Getting enough calories and nutrition while improving symptoms is the main goal in the treatment of gastroparesis. Many people can manage gastroparesis with dietary changes. Your healthcare professional may refer you to a specialist, called a dietitian.

A dietitian can work with you to find foods that are easier to digest. This can help you get enough nutrition from the food you eat.

A dietitian might have you try to the following:

- Eat smaller meals more often.

- Chew food well.

- Eat well-cooked fruits and vegetables rather than raw fruits and vegetables.

- Don't eat fruits and vegetables with a lot of fiber, such as oranges and broccoli. These can harden into a solid mass that stays in the stomach, called a bezoar.

- Choose mostly low-fat foods. If eating fat doesn't bother you, add small servings of fatty foods to your diet.

- Eat soups and pureed foods if liquids are easier for you to swallow.

- Drink about 34 to 51 ounces (1 to 1.5 liters) of water a day.

- Exercise gently, such as by taking a walk, after you eat.

- Don't drink fizzy drinks, called carbonated drinks, or alcohol.

- Don't smoke.

- Don't lie down for two hours after a meal.

- Take a multivitamin daily.

- Don't eat and drink at the same time. Space them out by about an hour.

Ask your dietitian for a list of foods suggested for people with gastroparesis.

Medications

Medicines to treat gastroparesis may include:

-

Medicines to help the stomach muscles work. Metoclopramide is the only medicine the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) has approved for the treatment of gastroparesis. The metoclopramide pill (Reglan) has a risk of serious side effects.

But the FDA recently approved a metoclopramide nasal spray (Gimoti) for treating diabetic gastroparesis. The nasal spray has fewer side effects than the pill.

Another medicine that helps the stomach muscles work is erythromycin. It may work less well over time. And it can cause side effects such as diarrhea.

There's a newer medicine, domperidone, that eases symptoms of gastroparesis. But the FDA doesn't approve the medicine except when other treatments have failed. To prescribe the medicine, healthcare professionals must apply to the FDA.

- Medicines to control nausea and vomiting. Drugs that help ease nausea and vomiting include diphenhydramine (Benadryl) and ondansetron. Prochlorperazine (Compro) is for nausea and vomiting that don't go away with other medicines.

Surgical treatment

Some people with gastroparesis may be unable to have any food or liquids. Then healthcare professionals may suggest that a feeding tube, called a jejunostomy tube, be placed in the small intestine. Another choice is a gastric venting tube to help relieve pressure from gastric contents.

Feeding tubes can be passed through the nose or mouth or directly into the small intestine through the skin. Most often, the tube is placed for the short term. A feeding tube is only for gastroparesis that's severe or when no other method controls blood sugar levels. Some people may need a feeding tube that goes into a vein in the chest, called an intravenous (IV) feeding tube.

Treatments under study

Researchers keep looking at new medicines and procedures to treat gastroparesis.

One new medicine in development is called relamorelin. The results of a phase 2 trial found that the drug could speed up gastric emptying and ease vomiting. The FDA has not yet approved the medicine, but study of it is ongoing.

Researchers also are studying new therapies that involve a slender tube, called an endoscope. The endoscope goes into the esophagus.

One procedure, known as endoscopic pyloromyotomy, involves making a cut in the muscular ring between the stomach and small intestine. This muscular ring is called the pylorus. It opens a channel from the stomach to the small intestine. The procedure also is called gastric peroral endoscopic myotomy (G-POEM). This procedure shows promise for gastroparesis. More study is needed.

Gastric electrical stimulation

In gastric electrical stimulation, a device that's put into the body with surgery gives electrical stimulation to the stomach muscles to move food better. Study results have been mixed. But the device seems to be most helpful for people who have diabetes and gastroparesis.

The FDA allows the device to be used for those who can't control their gastroparesis symptoms with diet changes or medicines. Larger studies are needed.

Lifestyle and home remedies

If you smoke, stop. Your gastroparesis symptoms are less likely to improve over time if you keep smoking.

Alternative medicine

Some alternative therapies have been used to treat gastroparesis, including acupuncture. Acupuncture involves putting very thin needles through the skin at certain points on the body. During a treatment called electroacupuncture, a small electrical current is passed through the needles. Studies have shown that these treatments may ease gastroparesis symptoms more than a sham treatment does.

Preparing for an appointment

You're likely to first see your main healthcare professional. You may then be sent to a doctor who specializes in digestive diseases, called a gastroenterologist. You also may see a specialist called a dietitian who can help you choose foods that are easier to digest.

What you can do

When you make the appointment ask if there's anything you need to do before, such as restrict your diet or stop using certain medicines. Take a family member or friend to the appointment, if possible, to help you remember the information you get.

Make a list of:

- Your symptoms. Include any that don't seem linked to the reason for your appointment and when they began.

- Key personal information. Include other medical conditions you have and recent life changes and major stresses.

- All medicines, vitamins or supplements you take. Include the doses and how often you take them.

- Questions to ask your healthcare team.

For gastroparesis, some basic questions to ask include:

- What's the most likely cause of my symptoms?

- What tests do I need?

- Is this condition likely to be long lasting?

- What treatments do you suggest?

- Are there certain foods I can eat that are easier to digest?

- I have other health conditions. How can I manage these conditions together?

- Are there brochures or other printed material that I can have? What websites do you suggest?

Be sure to ask all the questions you have.

What to expect from your doctor

Your healthcare professional might ask you:

- Do your symptoms come and go, or do you always have them?

- How bad are your symptoms?

- Does anything seem to make your symptoms better or worse?

- Did your symptoms start all of a sudden, such as after having food poisoning?

- What surgeries have you had?

© 1998-2025 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use