Overview

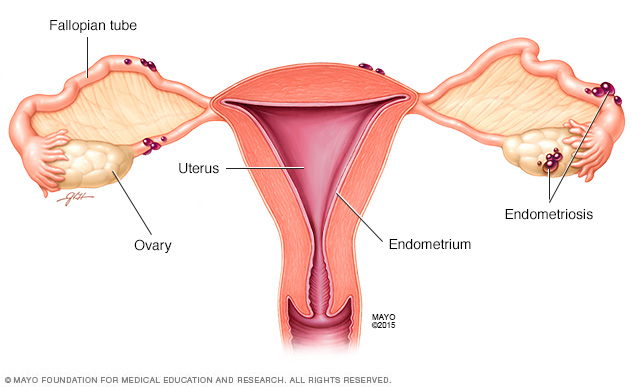

Endometriosis (en-doe-me-tree-O-sis) is an often-painful condition in which tissue that is similar to the inner lining of the uterus grows outside the uterus. It often affects the ovaries, fallopian tubes and the tissue lining the pelvis. Rarely, endometriosis growths may be found beyond the area where pelvic organs are located.

Endometriosis tissue acts as the lining inside the uterus would — it thickens, breaks down and bleeds with each menstrual cycle. But it grows in places where it doesn't belong, and it doesn't leave the body. When endometriosis involves the ovaries, cysts called endometriomas may form. Surrounding tissue can become irritated and form scar tissue. Bands of fibrous tissue called adhesions also may form. These can cause pelvic tissues and organs to stick to each other.

Endometriosis can cause pain, especially during menstrual periods. Fertility problems also may develop. But treatments can help you take charge of the condition and its complications.

Symptoms

The main symptom of endometriosis is pelvic pain. It's often linked with menstrual periods. Although many people have cramping during their periods, those with endometriosis often describe menstrual pain that's far worse than usual. The pain also may become worse over time.

Common symptoms of endometriosis include:

- Painful periods. Pelvic pain and cramping may start before a menstrual period and last for days into it. You also may have lower back and stomach pain. Another name for painful periods is dysmenorrhea.

- Pain with sex. Pain during or after sex is common with endometriosis.

- Pain with bowel movements or urination. You're most likely to have these symptoms before or during a menstrual period.

- Excessive bleeding. Sometimes, you may have heavy menstrual periods or bleeding between periods.

- Infertility. For some people, endometriosis is first found during tests for infertility treatment.

- Other symptoms. You may have fatigue, diarrhea, constipation, bloating or nausea. These symptoms are more common before or during menstrual periods.

The seriousness of your pain may not be a sign of the number or extent of endometriosis growths in your body. You could have a small amount of tissue with bad pain. Or you could have lots of endometriosis tissue with little or no pain.

Still, some people with endometriosis have no symptoms. Often, they find out they have the condition when they can't get pregnant or after they get surgery for another reason.

For those with symptoms, endometriosis sometimes may seem like other conditions that can cause pelvic pain. These include pelvic inflammatory disease or ovarian cysts. Or it may be confused with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which causes bouts of diarrhea, constipation and stomach cramps. IBS also can happen along with endometriosis. This makes it harder for your health care team to find the exact cause of your symptoms.

When to see a doctor

See a member of your health care team if you think you might have symptoms of endometriosis.

Endometriosis can be a challenge to manage. You may be better able to take charge of the symptoms if:

- Your care team finds the disease sooner rather than later.

- You learn as much as you can about endometriosis.

- You get treatment from a team of health care professionals from different medical fields, if needed.

Causes

The exact cause of endometriosis isn't clear. But some possible causes include:

- Retrograde menstruation. This is when menstrual blood flows back through the fallopian tubes and into the pelvic cavity instead of out of the body. The blood contains endometrial cells from the inner lining of the uterus. These cells may stick to the pelvic walls and surfaces of pelvic organs. There, they might grow and continue to thicken and bleed over the course of each menstrual cycle.

- Transformed peritoneal cells. Experts suggest that hormones or immune factors might help transform cells that line the inner side of the abdomen, called peritoneal cells, into cells that are like those that line the inside of the uterus.

- Embryonic cell changes. Hormones such as estrogen may transform embryonic cells — cells in the earliest stages of development — into endometrial-like cell growths during puberty.

- Surgical scar complication. Endometrial cells may attach to scar tissue from a cut made during surgery to the stomach area, such as a C-section.

- Endometrial cell transport. The blood vessels or tissue fluid system may move endometrial cells to other parts of the body.

- Immune system condition. A problem with the immune system may make the body unable to recognize and destroy endometriosis tissue.

Risk factors

Factors that raise the risk of endometriosis include:

- Never giving birth.

- Starting your period at an early age.

- Going through menopause at an older age.

- Short menstrual cycles — for instance, less than 27 days.

- Heavy menstrual periods that last longer than seven days.

- Having higher levels of estrogen in your body or a greater lifetime exposure to estrogen your body produces.

- Low body mass index.

- One or more relatives with endometriosis, such as a mother, aunt or sister.

Any health condition that prevents blood from flowing out of the body during menstrual periods also can be an endometriosis risk factor. So can conditions of the reproductive tract.

Endometriosis symptoms often happen years after menstruation starts. The symptoms may get better for a time with pregnancy. Pain may become milder over time with menopause, unless you take estrogen therapy.

Complications

Infertility

The main complication of endometriosis is trouble getting pregnant, also called infertility. Up to half of people with endometriosis have a hard time conceiving.

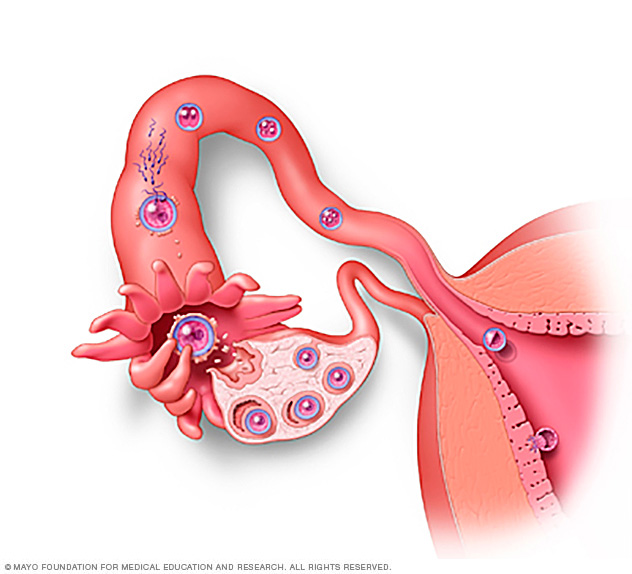

For pregnancy to happen, an egg must be released from an ovary. Then the egg has to travel through the fallopian tube and become fertilized by a sperm cell. The fertilized egg then needs to attach itself to the wall of the uterus to start developing. Endometriosis may block the tube and keep the egg and sperm from uniting. But the condition also seems to affect fertility in less-direct ways. For instance, it may damage the sperm or egg.

Even so, many with mild to moderate endometriosis can still conceive and carry a pregnancy to term. Health care professionals sometimes advise those with endometriosis not to delay having children. That's because the condition may become worse with time.

Cancer

Some studies suggest that endometriosis raises the risk of ovarian cancer. But the overall lifetime risk of ovarian cancer is low to begin with. And it stays fairly low in people with endometriosis. Although rare, another type of cancer called endometriosis-associated adenocarcinoma can happen later in life in those who've had endometriosis.

Diagnosis

To find out if you have endometriosis, your doctor will likely start by giving you a physical exam. You'll be asked to describe your symptoms, including where and when you feel pain.

Tests to check for clues of endometriosis include:

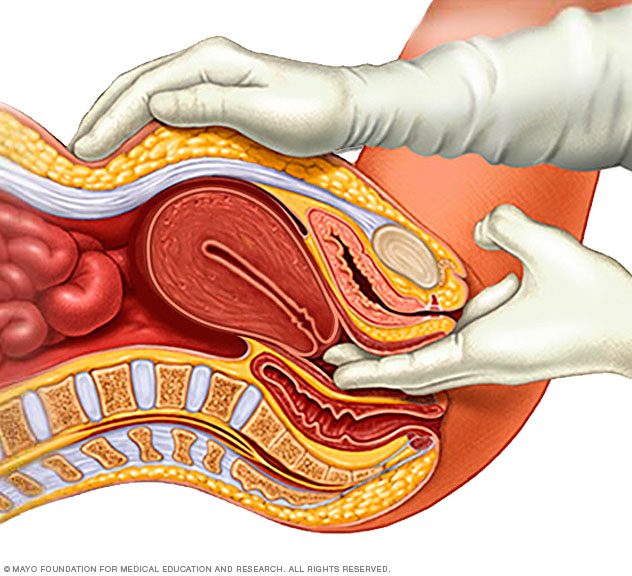

- Pelvic exam. Your health care professional feels areas in your pelvis with one or two gloved fingers to check for any unusual changes. These changes can include cysts on the reproductive organs, painful spots, irregular growths called nodules and scars behind the uterus. Often, small areas of endometriosis can't be felt unless a cyst has formed.

- Ultrasound. This test uses sound waves to make pictures of the inside of the body. To capture the images, a device called a transducer might be pressed against the stomach area. Or it may be placed into the vagina in a version of the exam called transvaginal ultrasound. Both types of the test may be done to get the best view of the reproductive organs. A standard ultrasound won't confirm whether you have endometriosis. But it can find cysts linked with the condition called endometriomas.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This exam uses a magnetic field and radio waves to make images of the organs and tissues within the body. For some, an MRI helps with surgical planning. It gives your surgeon detailed information about the location and size of endometriosis growths.

-

Laparoscopy. In some cases, you may be referred to a surgeon for this procedure. Laparoscopy lets the surgeon check inside your abdomen for signs of endometriosis tissue. Before the surgery, you receive medicine that puts you a sleep-like state and prevents pain. Then your surgeon makes a tiny cut near your navel and inserts a slender viewing instrument called a laparoscope.

A laparoscopy can provide information about the location, extent and size of the endometriosis growths. Your surgeon may take a tissue sample called biopsy for more testing. With proper planning, a surgeon can often treat endometriosis during the laparoscopy so that you need only one surgery.

Treatment

Treatment for endometriosis often involves medicine or surgery. The approach you and your health care team choose will depend on how serious your symptoms are and whether you hope to become pregnant.

Typically, medicine is recommended first. If it doesn't help enough, surgery becomes an option.

Pain medicines

Your health care team may recommend pain relievers that you can buy without a prescription. These medicines include the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) or naproxen sodium (Aleve). They can help ease painful menstrual cramps.

Your care team may recommend hormone therapy along with pain relievers if you're not trying to get pregnant.

Hormone therapy

Sometimes, hormone medicine help ease or get rid of endometriosis pain. The rise and fall of hormones during the menstrual cycle causes endometriosis tissue to thicken, break down and bleed. Lab-made versions of hormones may slow the growth of this tissue and prevent new tissue from forming.

Hormone therapy isn't a permanent fix for endometriosis. The symptoms could come back after you stop treatment.

Therapies used to treat endometriosis include:

- Hormonal contraceptives. Birth control pills, shots, patches and vaginal rings help control the hormones that stimulate endometriosis. Many have lighter and shorter menstrual flow when they use hormonal birth control. Using hormonal contraceptives may ease or get rid of pain in some cases. The chances of relief seem to go up if you use birth control pills for a year or more with no breaks.

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (Gn-RH) agonists and antagonists. These medicines block the menstrual cycle and lower estrogen levels. This causes endometriosis tissue to shrink. These medicines create an artificial menopause. Taking a low dose of estrogen or progestin along with Gn-RH agonists and antagonists may ease menopausal side effects. Those include hot flashes, vaginal dryness and bone loss. Menstrual periods and the ability to get pregnant return when you stop taking the medicine.

- Progestin therapy. Progestin is a lab-made version of a hormone that plays a role in the menstrual cycle and pregnancy. A variety of progestin treatments can stop menstrual periods and the growth of endometriosis tissue, which may relieve symptoms. Progestin therapies include a tiny device placed in the uterus that releases levonorgestrel (Mirena, Skyla, others), a contraceptive rod placed under the skin of the arm (Nexplanon), birth control shots (Depo-Provera) or a progestin-only birth control pill (Camila, Slynd).

- Aromatase inhibitors. These are a class of medicines that lower the amount of estrogen in the body. Your health care team may recommend an aromatase inhibitor along with a progestin or combination birth control pills to treat endometriosis.

Conservative surgery

Conservative surgery removes endometriosis tissue. It aims to preserve the uterus and the ovaries. If you have endometriosis and you're trying to become pregnant, this type of surgery may boost your chances of success. It also may help if the condition causes you terrible pain — but endometriosis and pain may come back over time after surgery.

Your surgeon may do this procedure with small cuts, also called laparoscopic surgery. Less often, surgery that involves a larger cut in the abdomen is needed to remove thick bands of scar tissue. But even in severe cases of endometriosis, most can be treated with the laparoscopic method.

During laparoscopic surgery, your surgeon places a slender viewing instrument called a laparoscope through a small cut near your navel. Surgical tools are inserted to remove endometriosis tissue through another small cut. Some surgeons do laparoscopy with help from robotic devices that they control. After surgery, your health care team may recommend taking hormone medicine to help improve pain.

Fertility treatment

Endometriosis can lead to trouble getting pregnant. If you have a hard time conceiving, your health care team may recommend fertility treatment. You might be referred to a doctor who treats infertility, called a reproductive endocrinologist. Fertility treatment can include medicine that helps ovaries make more eggs. It also can include a series of procedures that mix eggs and sperm outside the body, called in vitro fertilization. The treatment that's right for you depends on your personal situation.

Hysterectomy with removal of the ovaries

Hysterectomy is surgery to remove the uterus. Taking out the uterus and ovaries was once thought to be the most effective treatment for endometriosis. Today, some experts consider it to be a last resort to ease pain when other treatments haven't worked. Other experts instead recommend surgery that focuses on the careful and thorough removal of all endometriosis tissue.

Having the ovaries removed, also called oophorectomy, causes early menopause. The lack of hormones made by the ovaries may improve endometriosis pain for some. But for others, endometriosis that remains after surgery continues to cause symptoms. Early menopause also carries a risk of heart and blood vessel diseases, certain metabolic conditions and early death.

In people who don't want to get pregnant, hysterectomy sometimes can be used to treat symptoms linked with endometriosis. These include heavy menstrual bleeding and painful menses due to uterine cramping. Even when the ovaries are left in place, a hysterectomy may still have a long-term effect on your health. That's especially true if you have the surgery before age 35.

To manage and treat endometriosis, it's key to find a health care professional with whom you feel comfortable. You may want to get a second opinion before you start any treatment. That way, you can be sure you know all of your options and the pros and cons of each.

Lifestyle and home remedies

It may take time to find a treatment that works. Until then, you can try some things at home to ease your pain.

- Warm baths and a heating pad can help relax pelvic muscles. This lessens cramping and pain.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can help ease painful menstrual cramps. NSAIDs include ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) and naproxen sodium (Aleve).

You also can ask your health care team if physical therapy might help. A therapist can teach you how to relax muscles that support the uterus, called the pelvic floor. Relaxing these tight muscles may help pelvic pain linked with endometriosis feel less intense.

Alternative medicine

Alternative medicine involves treatments that aren't part of standard medical care. Some people with endometriosis say they get pain relief from alternative therapies such as:

- Acupuncture, in which a trained practitioner places fine needles into the skin.

- Chiropractic care, in which a licensed professional adjusts the spine or other body parts.

- Herbs such as cinnamon trig or licorice root.

- Supplements including vitamin B1, magnesium or omega-3 fatty acids.

Acupuncture has shown some promise at easing endometriosis pain. But overall, there's little research on much relief people with the condition might get from alternative medicine. Always check with your health care team before you try a new alternative therapy to find out if it's safe for you. For example, supplements and herbs can affect standard treatments such as medicines. If you're interested in trying acupuncture or chiropractic care, ask your care team to recommend reputable professionals. Check with your insurance company to see if the expense will be covered.

Coping and support

Think about joining a support group if you have endometriosis or a complication such as fertility trouble. Sometimes it helps simply to talk to other people who can relate to your feelings and experiences. If you can't find a support group in your community, look for one online.

Preparing for an appointment

Your first appointment will likely be with either your primary care doctor or a gynecologist. If you're seeking treatment for infertility, you may be referred to a doctor called a reproductive endocrinologist.

Appointments can be brief, and it can be hard to remember everything you want to discuss. So it's a good idea to plan ahead for your appointment.

What you can do

- Make a list of any symptoms you have. Include all of your symptoms, even if you don't think they're related to the reason for your appointment.

- Make a list of any medicines, herbs or vitamin supplements you take. Include how often you take them and how much you take, called the dose.

- Have a family member or close friend join you, if possible. You may get a lot of information at your visit, and it can be hard to recall everything.

- Take a notepad or electronic device with you. Use it to make notes of important information during your visit.

- Prepare a list of questions to ask your doctor. List your most important questions first, to be sure you bring up those points.

For endometriosis, some basic questions to ask your doctor include:

- How is endometriosis diagnosed?

- What medicines treat endometriosis? Is there a medicine that can ease my symptoms?

- What side effects can I expect from medicine?

- Do you recommend surgery?

- Will endometriosis affect my ability to become pregnant?

- Can treatment of endometriosis improve my fertility?

- Can you recommend any alternative treatments I might try?

Make sure that you understand everything your health care team tells you. It's fine to ask your team to repeat information or to ask follow-up questions.

What to expect from your doctor

Some questions your doctor might ask include:

- How often do you have these symptoms?

- How long have you had these symptoms?

- How bad are your symptoms?

- Do your symptoms seem to be related to your menstrual cycle?

- Does anything improve your symptoms?

- Does anything make your symptoms worse?

© 1998-2025 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use