Overview

Dressler syndrome is swelling and irritation of the sac around the heart that happens after damage to the heart muscle. The damage may trigger an immune system response that causes the condition. The damage can result from a heart attack, heart surgery or a serious injury.

Symptoms of Dressler syndrome include chest pain that can feel like chest pain from a heart attack.

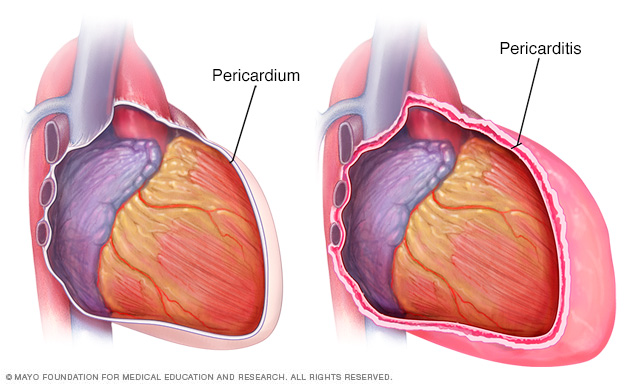

Swelling and irritation of the sac around the heart is called pericarditis. Dressler syndrome is a type of pericarditis that can start after the heart muscle is damaged. So you may hear Dressler syndrome called post-traumatic pericarditis.

Some other names for the condition are:

- Post-myocardial infarction syndrome.

- Post-cardiac injury syndrome.

- Post-pericardiotomy syndrome.

Symptoms

Symptoms of Dressler syndrome are likely to start weeks to a few months after a heart attack, surgery or injury to the chest. Symptoms can include:

- Chest pain, which may get worse with deep breaths.

- Fever.

- Shortness of breath.

When to see a doctor

Get emergency care for sudden or ongoing chest pain. This can be a symptom of a heart attack or another serious condition.

Causes

Experts think Dressler syndrome is caused by the immune system's response to heart damage. The body reacts to the injured tissue by sending immune cells and proteins called antibodies to clean up and repair the affected area. Sometimes this response causes swelling due to the inflammation in the sac around the heart that's known as the pericardium.

Dressler syndrome can happen after a heart attack or some heart surgeries or procedures. It also can happen after a serious injury to the chest, such as trauma from a car accident.

Risk factors

Damage to the heart muscle increases the risk of Dressler syndrome. Some things that cause heart muscle are:

- Chest injury.

- Some types of heart surgery.

- Heart attack.

Complications

A complication of Dressler syndrome is fluid buildup in the tissues surrounding the lungs called pleural effusion.

Rarely, Dressler syndrome can cause more-serious complications, including:

- Cardiac tamponade. Swelling of the pericardium can cause fluid to build up in the sac. The fluid can put pressure on the heart. The pressure forces the heart to work harder, and the heart doesn't pump blood as well as it should.

- Constrictive pericarditis. Swelling that's ongoing or that keeps coming back can cause the pericardium to become thick or scarred. The scarring can reduce the heart's ability to pump blood.

Prevention

Some studies suggest that taking the anti-inflammatory medicine colchicine (Colcrys, Gloperba, others) soon after heart surgery may help prevent Dressler syndrome.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of Dressler syndrome starts with a physical exam from your healthcare professional. The exams includes listening to the heart with a device called a stethoscope. A sound called a pericardial rub can happen when the pericardium is inflamed or when fluid has collected around the heart.

Tests that can help find out if you have Dressler syndrome include:

- Complete blood count. Most people with Dressler syndrome have an increased white blood cell count.

- Blood tests to measure inflammation. A blood test can check the level of C-reactive protein made by the liver. A higher level of this protein can be a sign of inflammation that's linked with Dressler syndrome. Another blood test called erythrocyte sedimentation rate measures how fast red blood cells sink to the bottom of a test tube. When they sink fast, it can be a sign of more inflammation.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG). This quick test checks the electrical activity of the heart. It shows how the heart is beating. Sticky patches called electrodes attach to the chest and sometimes the arms and legs. Wires connect the electrodes to a computer that prints or displays the test results. Certain changes in the heart's electrical signals can be a sign of pressure on the heart. But these changes can happen after heart surgery, so the results of other tests are needed to confirm whether you have Dressler syndrome.

- Chest X-ray. A chest X-ray can help detect fluid around the heart or lungs. It also can help find out if the fluid is caused by a different condition, such as pneumonia.

- Echocardiogram. Sound waves make an image of the heart to show if fluid is collecting around it.

- Cardiac MRI. This test uses sound waves to create still or moving pictures of how blood flows through the heart. This test can show thickening of the pericardium.

Treatment

The goals of treatment for Dressler syndrome are to manage pain and lower the inflammation. Treatment may involve medicines. Surgery may be needed if complications happen.

Medications

The main treatment for Dressler syndrome is medicine to lower inflammation, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as:

- Aspirin.

- Ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others).

- Colchicine (Colcrys, Gloperba, others).

If Dressler syndrome happens after a heart attack, usually aspirin is preferred over other NSAIDs.

Indomethacin also may be given.

If those medicines don't help, the next step might be corticosteroids. These can lower inflammation linked with Dressler syndrome by turning down the immune system.

Corticosteroids can have serious side effects. And they might interfere with the healing of damaged heart tissue after a heart attack or surgery. For those reasons, corticosteroids tend to be used only when other treatments don't work.

Surgery or other procedures

Other treatments may be needed to treat complications of Dressler syndrome. These include:

- Draining excess fluids. For cardiac tamponade, the excess fluid can be removed with a needle or a small tube called a catheter. This treatment is called pericardiocentesis. It's usually done using medicine called a local anesthetic that numbs a specific part of the body.

- Removing the pericardium. For constrictive pericarditis, treatment might involve surgery to remove the pericardium. The surgery is called pericardiectomy.

Preparing for an appointment

If you're being seen in the emergency room for chest pain, you might be asked:

- When did your symptoms begin?

- How bad is your chest pain on a scale of 1 to 10?

- Does anything make your symptoms worse? For example, does it hurt more when you take a deep breath?

- Where is the pain? Does it go anywhere beyond your chest?

- Have you recently had a heart attack, heart surgery or blunt trauma to your chest?

- Do you have a history of heart disease?

- What medicines do you take?

© 1998-2025 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use