Overview

Cardiomyopathy (kahr-dee-o-my-OP-uh-thee) is a disease of the heart muscle. It causes the heart to have a harder time pumping blood to the rest of the body, which can lead to symptoms of heart failure. Cardiomyopathy also can lead to some other serious heart conditions.

There are various types of cardiomyopathy. The main types include dilated, hypertrophic and restrictive cardiomyopathy. Treatment includes medicines and sometimes surgically implanted devices and heart surgery. Some people with severe cardiomyopathy need a heart transplant. Treatment depends on the type of cardiomyopathy and how serious it is.

Symptoms

Some people with cardiomyopathy don't ever get symptoms. For others, symptoms appear as the condition becomes worse. Cardiomyopathy symptoms can include:

- Shortness of breath or trouble breathing with activity or even at rest.

- Chest pain, especially after physical activity or heavy meals.

- Heartbeats that feel rapid, pounding or fluttering.

- Swelling of the legs, ankles, feet, stomach area and neck veins.

- Bloating of the stomach area due to fluid buildup.

- Cough while lying down.

- Trouble lying flat to sleep.

- Fatigue, even after getting rest.

- Dizziness.

- Fainting.

Symptoms tend to get worse unless they are treated. In some people, the condition becomes worse quickly. In others, it might not become worse for a long time.

When to see a doctor

See your healthcare professional if you have any symptoms of cardiomyopathy. Call 911 or your local emergency number if you faint, have trouble breathing or have chest pain that lasts for more than a few minutes.

Some types of cardiomyopathy can be passed down through families. If you have the condition, your healthcare professional might recommend that your family members be checked.

Causes

Often, the cause of the cardiomyopathy isn't known. But some people get it due to another condition. This is known as acquired cardiomyopathy. Other people are born with cardiomyopathy because of a gene passed on from a parent. This is called inherited cardiomyopathy.

Certain health conditions or behaviors that can lead to acquired cardiomyopathy include:

- Long-term high blood pressure.

- Heart tissue damage from a heart attack.

- Long-term rapid heart rate.

- Heart valve problems.

- COVID-19 infection.

- Certain infections, especially those that cause inflammation of the heart.

- Metabolic disorders, such as obesity, thyroid disease or diabetes.

- Lack of essential vitamins or minerals in the diet, such as thiamin (vitamin B-1).

- Pregnancy complications.

- Iron buildup in the heart muscle, called hemochromatosis.

- The growth of tiny lumps of inflammatory cells called granulomas in any part of the body. When this happens in the heart or lungs, it's called sarcoidosis.

- The buildup of irregular proteins in the organs, called amyloidosis.

- Connective tissue disorders.

- Drinking too much alcohol over many years.

- Use of cocaine, amphetamines or anabolic steroids.

- Use of some chemotherapy medicines and radiation to treat cancer.

Types of cardiomyopathy include:

-

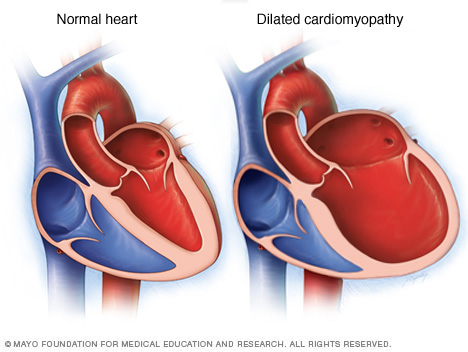

Dilated cardiomyopathy. In this type of cardiomyopathy, the heart's chambers thin and stretch, growing larger. The condition tends to start in the heart's main pumping chamber, called the left ventricle. As a result, the heart has trouble pumping blood to the rest of the body.

This type can affect people of all ages. But it happens most often in people younger than 50 and is more likely to affect men. Conditions that can lead to a dilated heart include coronary artery disease and heart attack. But for some people, gene changes play a role in the disease.

-

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. In this type, the heart muscle becomes thickened. This makes it harder for the heart to work. The condition mostly affects the muscle of the heart's main pumping chamber.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy can start at any age. But it tends to be worse if it happens during childhood. Most people with this type of cardiomyopathy have a family history of the disease. Some gene changes have been linked to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The condition doesn't happen due to a heart problem.

-

Restrictive cardiomyopathy. In this type, the heart muscle becomes stiff and less flexible. As a result, it can't expand and fill with blood between heartbeats. This least common type of cardiomyopathy can happen at any age. But it most often affects older people.

Restrictive cardiomyopathy can occur for no known reason, also called an idiopathic cause. Or it can by caused by a disease elsewhere in the body that affects the heart, such as amyloidosis.

- Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC). This is a rare type of cardiomyopathy that tends to happen between the ages of 10 and 50. It mainly affects the muscle in the lower right heart chamber, called the right ventricle. The muscle is replaced by fat that can become scarred. This can lead to heart rhythm problems. Sometimes, the condition involves the left ventricle as well. ARVC often is caused by gene changes.

- Unclassified cardiomyopathy. Other types of cardiomyopathy fall into this group.

Risk factors

Many things can raise the risk of cardiomyopathy, including:

- Family history of cardiomyopathy, heart failure and sudden cardiac arrest.

- Long-term high blood pressure.

- Conditions that affect the heart. These include a past heart attack, coronary artery disease or an infection in the heart.

- Obesity, which makes the heart work harder.

- Long-term alcohol misuse.

- Illicit drug use, such as cocaine, amphetamines and anabolic steroids.

- Treatment with certain chemotherapy medicines and radiation for cancer.

Many diseases also raise the risk of cardiomyopathy, including:

- Diabetes.

- Thyroid disease.

- Storage of excess iron in the body, called hemochromatosis.

- Buildup of a certain protein in organs, called amyloidosis.

- The growth of small patches of inflamed tissue in organs, called sarcoidosis.

- Connective tissue disorders.

Complications

Cardiomyopathy can lead to serious medical conditions, including:

- Heart failure. The heart can't pump enough blood to meet the body's needs. Without treatment, heart failure can be life-threatening.

- Blood clots. Because the heart can't pump well, blood clots might form in the heart. If clots enter the bloodstream, they can block the blood flow to other organs, including the heart and brain.

- Heart valve problems. Because cardiomyopathy can cause the heart to become larger, the heart valves might not close properly. This can cause blood to flow backward in the valve.

- Cardiac arrest and sudden death. Cardiomyopathy can trigger irregular heart rhythms that cause fainting. Sometimes, irregular heartbeats can cause sudden death if the heart stops beating effectively.

Prevention

Inherited types of cardiomyopathy can't be prevented. Let your healthcare professional know if you have a family history of the condition.

You can help lower the risk of acquired types of cardiomyopathy, which are caused by other conditions. Take steps to lead a heart-healthy lifestyle, including:

- Stay away from alcohol or illegal drugs such as cocaine.

- Control any other conditions you have, such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol or diabetes.

- Eat a healthy diet.

- Get regular exercise.

- Get enough sleep.

- Lower your stress.

These healthy habits also can help people with inherited cardiomyopathy control their symptoms.

Diagnosis

Your healthcare professional examines you and usually ask questions about your personal and family medical history. You may be asked when your symptoms happen — for example, whether exercise triggers your symptoms.

Tests

Tests to diagnose cardiomyopathy may include:

- Blood tests. Blood tests may be done to check iron levels and to see how well the kidney, thyroid and liver are working. One blood test can measure a protein made in the heart called B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP). A blood level of BNP might rise during heart failure, a common complication of cardiomyopathy.

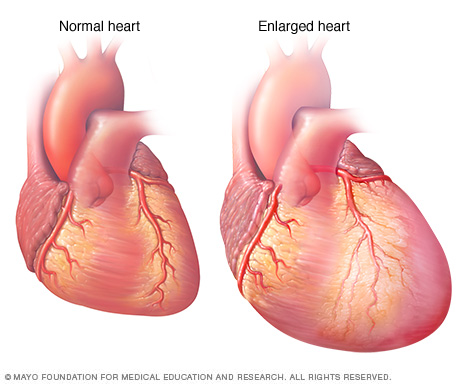

- Chest X-ray. A chest X-ray shows the condition of the lungs and heart. It can show whether the heart is enlarged.

- Echocardiogram. Sound waves are used to create images of the beating heart. This test can show how blood flows through the heart and heart valves.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG). This quick and painless test measures the electrical activity of the heart. Sticky patches called electrodes are placed on the chest and sometimes the arms and legs. Wires connect the electrodes to a computer, which prints or displays the test results. An ECG can show the heart rhythm and how slow or fast the heart is beating.

- Exercise stress tests. These tests often involve walking on a treadmill or pedaling a stationary bike while the heart is monitored. The tests show how the heart reacts to exercise. If you can't exercise, you may be given medicine that increases the heart rate like exercise does. Sometimes echocardiogram is done during a stress test.

-

Cardiac catheterization. A thin tube called a catheter is placed into the groin and threaded through blood vessels to the heart. Pressure within the chambers of the heart can be measured to see how forcefully blood pumps through the heart. Dye can be injected through the catheter into blood vessels to make them easier to see on X-rays. This is called a coronary angiogram. Cardiac catheterization can reveal blockages in blood vessels.

This test also might involve removing a small tissue sample from the heart for a lab to check. That procedure is called a biopsy.

- Cardiac MRI. This test uses magnetic fields and radio waves to make images of the heart. This test may be done if the images from an echocardiogram aren't enough to confirm cardiomyopathy.

- Cardiac CT scan. A series of X-rays are used to create images of the heart and chest. The test shows the size of the heart and the heart valves. A CT scan of the heart also can show calcium deposits and blockages in the heart arteries.

- Genetic testing or screening. Cardiomyopathy can be passed down through families, also called inherited cardiomyopathy. Ask your healthcare professional if genetic testing is right for you. Family screening or genetic testing might include first-degree relatives — parents, siblings and children.

Treatment

The goals of cardiomyopathy treatment are to:

- Manage symptoms.

- Keep the condition from getting worse.

- Lower the risk of complications.

The type of treatment depends on the type of cardiomyopathy and how serious it is.

Medications

Many types of medicines are used to treat cardiomyopathy. Medicines for cardiomyopathy can help:

- Improve the heart's ability to pump blood.

- Improve blood flow.

- Lower blood pressure.

- Slow heart rate.

- Remove extra fluid and sodium from the body.

- Prevent blood clots.

Therapies

Ways to treat cardiomyopathy or an irregular heartbeat without surgery include:

- Septal ablation. This shrinks a small part of the thickened heart muscle. It's a treatment option for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A doctor threads a thin tube called a catheter to the affected area. Then, alcohol flows through the tube into the artery that sends blood to that area. Septal ablation lets blood flow through the area.

- Other types of ablation. A doctor places one or more catheters into blood vessels to the heart. Sensors at the catheter tips use heat or cold energy to create tiny scars in the heart. The scars block irregular heart signals and restore the heartbeat.

Surgery or other procedures

Somes types of devices can be placed in the heart with surgery. They can help the heart work better and relieve symptoms. Some help prevent complications. Types of cardiac devices include:

- Ventricular assist device (VAD). A VAD helps pump blood from the lower chambers of the heart to the rest of the body. It's also called a mechanical circulatory support device. Most often, a VAD is considered after less invasive treatments don't help. It can be used as a long-term treatment or as a short-term treatment while waiting for a heart transplant.

- Pacemaker. A pacemaker is a small device that's placed in the chest to help control the heartbeat.

- Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) device. This device can help the chambers of the heart squeeze in a way that's more organized and efficient. It's a treatment option for some people with dilated cardiomyopathy. It can help those with ongoing symptoms, along with signs of a condition called left bundle branch block. The condition causes a delay or blockage along the pathway that electrical signals travel to make the heart beat.

- Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD). This device may be recommended to prevent sudden cardiac arrest, which is a dangerous complication of cardiomyopathy. An ICD tracks heart rhythm and gives electric shocks when needed to control irregular heart rhythms. An ICD doesn't treat cardiomyopathy. Rather, it watches for and controls irregular rhythms.

Types of surgery used to treat cardiomyopathy include:

- Septal myectomy. This is a type of open-heart surgery that can treat hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A surgeon removes part of the thickened heart muscle wall, called a septum, that separates the two bottom heart chambers, called ventricles. Removing part of the heart muscle improves blood flow through the heart. It also improves a type of heart valve disease called mitral valve regurgitation.

- Heart transplant. This is surgery to replace a diseased heart with a donor's healthy heart. It can be a treatment option for end-stage heart failure, when medicines and other treatments no longer work.

Lifestyle and home remedies

These lifestyle changes can help you manage cardiomyopathy:

- Don't smoke. If you smoke, quit. You can ask your healthcare professional for help.

- Lose weight if you're overweight. Ask your care team what a healthy weight is for you.

- Get regular exercise. Talk to your healthcare professional about the safest type and amount for you.

- Eat a healthy diet. Include a variety of fruits, vegetables and whole grains.

- Use less salt. Cut back on foods that are high in sodium. Aim for less than 1,500 milligrams of sodium a day.

- Avoid or limit alcohol.

- Manage stress.

- Get enough sleep.

- Take all medicines as prescribed.

- Get regular health checkups.

Preparing for an appointment

If you think you may have cardiomyopathy or are worried about your risk, make an appointment with your healthcare professional. You may be referred to a heart doctor, also called a cardiologist.

Here's information to help you get ready for your appointment.

What you can do

Be aware of any restrictions that your healthcare professional wants you to follow before your appointment. When you make the appointment, ask if there's anything you need to do in advance, such as avoid certain foods or drinks.

Make a list of:

- Your symptoms. Include any that may not seem related to cardiomyopathy. Note when your symptoms began.

- Important personal information. Include any family history of cardiomyopathy, heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure or diabetes. Also note any major stresses or recent life changes.

- All medicines, vitamins or other supplements you take, including the doses.

- Questions to ask your healthcare team.

Take a family member or friend along, if you can. This person can help you remember the information you're given.

For cardiomyopathy, some basic questions to ask your healthcare professional include:

- What's the most likely cause of my symptoms?

- What are other possible causes?

- What tests do I need?

- What treatment options are available, and which do you recommend for me?

- How often should I be tested for cardiomyopathy?

- Should I tell my family members to be tested for cardiomyopathy?

- I have other health conditions. How can I best manage these conditions together?

- Are there brochures or other printed material that I can have? What websites do you recommend?

What to expect from your doctor

Your healthcare team is likely to ask you questions such as:

- Do you have symptoms all the time, or do they come and go?

- How serious are your symptoms?

- What, if anything, seems to improve your symptoms?

- What, if anything, appears to make your symptoms worse?

© 1998-2025 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use