Overview

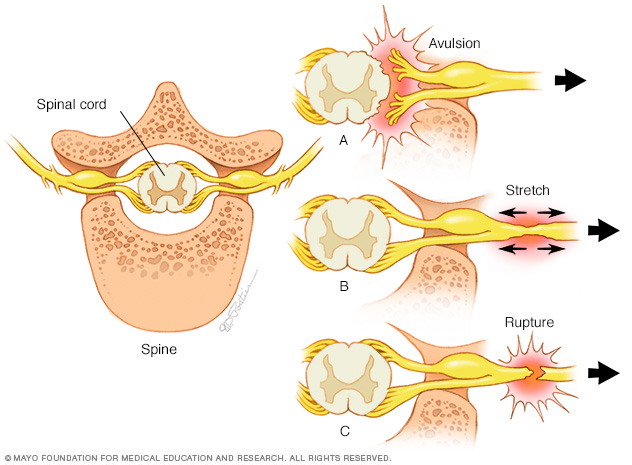

The brachial plexus is the group of nerves that sends signals from the spinal cord to the shoulder, arm and hand. A brachial plexus injury happens when these nerves are stretched, squeezed together, or in the most serious cases, ripped apart or torn away from the spinal cord.

Minor brachial plexus injuries, called stingers or burners, are common in contact sports, such as football. Babies sometimes get brachial plexus injuries when they're born. Other health issues, such as inflammation or tumors, may affect the brachial plexus.

The most serious brachial plexus injuries happen during car or motorcycle accidents. Bad brachial plexus injuries can leave the arm paralyzed, but surgery may help.

Symptoms

Symptoms of a brachial plexus injury can differ depending on how serious the injury is and where it's located. Usually only one arm is affected.

Less severe injuries

Minor damage often happens during contact sports, such as football or wrestling, when the brachial plexus nerves get stretched or squeezed together. These are called stingers or burners. Some of the symptoms are:

- A feeling like an electric shock or a burning sensation shooting down the arm.

- Numbness and weakness in the arm.

These symptoms usually last only a few seconds or minutes, but in some people the symptoms may last for days or longer.

More-serious injuries

More-serious symptoms happen when an injury seriously damages or even tears or ruptures the nerves. The most serious brachial plexus injury is when the nerve root is cut or torn from the spinal cord.

Symptoms of serious injuries can include:

- Weakness or not being able to use certain muscles in the hand, arm or shoulder.

- Loss of feeling in the arm, including the shoulder and hand.

- Intense pain.

When to see a doctor

Brachial plexus injuries can cause lasting weakness or disability. Even if yours seems minor, you may need medical care. See your healthcare provider if you have:

- Burners and stingers that keep coming back, or symptoms that don't go away quickly.

- Weakness in the hand or arm.

- Neck pain.

- Symptoms in both arms.

Causes

Brachial plexus injuries in the upper nerves happen when the shoulder is forced down on one side of the body and the head is pushed to the other side in the opposite direction. The lower nerves are more likely to be injured when the arm is forced above the head.

These injuries can happen in many ways, including:

- Contact sports. Many football players have burners or stingers. These are caused when the brachial plexus nerves get stretched past their limit during clashes with other players.

- Birth. Newborns can have brachial plexus injuries. This is more common in babies with a high birth weight, a very long labor and a bottom-first, also called breech, presentation. If a baby's shoulders get stuck in the birth canal, brachial plexus palsy is more likely. Most often, the upper nerves are injured. This is called Erb palsy.

- Injuries. Many injuries — including those from motor vehicle accidents, motorcycle accidents, falls or bullet wounds — can damage the brachial plexus.

- Tumors and cancer treatments. Tumors can grow on their own. Rarely, they can form because of a health condition, such as neurofibromatosis, or after radiation treatment.

Risk factors

Playing contact sports, especially football and wrestling, or being in high-speed motor vehicle accidents increases the risk of brachial plexus injury.

Complications

Many mild brachial plexus injuries heal over time with few to no issues. But some injuries can cause short-term or lasting problems, such as:

- Stiff joints. If you have hand or arm paralysis, the joints can get stiff. This can make it hard to move, even if you are able to use your hand or arm again. For that reason, your healthcare professional may suggest ongoing physical therapy during your recovery.

- Pain. This is caused by nerve damage and may be lifelong.

- Numbness. If you lose feeling in the arm or hand, you're at risk of burning or injuring yourself without knowing it.

- Muscle atrophy. Nerves regrow slowly and can take many years to heal after injury. During that time, not using your muscles may cause them to break down.

- Permanent disability. How well you recover from a serious brachial plexus injury depends on many things, such as your age and the type, location and seriousness of the injury. Even with surgery, some people have muscle weakness or paralysis that lasts for the rest of their lives.

Prevention

Although a brachial plexus injury can't always be avoided, you can take steps to reduce your risk of complications after getting hurt:

-

For yourself. If you can't use the hand or arm for a short time, daily range-of-motion exercises and physical therapy can help prevent joint stiffness. Avoid burns or cuts, as you may not feel them if you have numbness.

If you're an athlete with a brachial plexus injury, your healthcare professional may suggest that you wear padding to protect the area when you play sports.

- For your child. If your child has brachial plexus palsy, it's important to exercise your child's joints and working muscles every day. You can start when your baby is just a few weeks old. This helps stop the joints from becoming permanently stiff. It also keeps your child's working muscles strong and healthy.

Diagnosis

To diagnose your condition, your healthcare professional checks your symptoms and does a physical exam. To know how serious your brachial plexus injury is, you may need one or more of the following tests:

- X-ray. An X-ray of the shoulder and neck can show fractures or other related injuries.

- Electromyography (EMG). During an EMG, a healthcare professional places a needle electrode through the skin into different muscles. The test looks at the electrical activity of the muscles when they tighten and when they're at rest. You may feel a little pain when the electrodes are put in, but most people can finish the test without much discomfort.

- Nerve conduction studies. These tests are usually done as part of EMG. They measure how fast and how well electrical signals travel down the nerves. This provides information about how well the nerve is working.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This test uses a powerful magnetic field and radio waves to make very detailed images of the organs and tissues in the body. It can show how much damage there is to the brachial plexus after an injury. It also can show any artery damage in the limb, which is important for reconstruction. New types of high-resolution MRI, such as magnetic resonance neurography or diffusion tensor imaging, may be used.

- Computerized tomography (CT) myelography. Computerized tomography uses a series of X-rays to create images of the body. CT myelography uses contrast dye, injected during a spinal tap, to look for issues in the spinal cord and nerve roots. This test is sometimes done when MRIs don't give enough information.

Treatment

Treatment depends on many factors, such as the seriousness of the injury, the type of injury, the length of time since the injury and other existing conditions.

Nerves that have only been stretched may heal on their own.

Your healthcare team may suggest physical therapy to keep the joints and muscles working properly, maintain range of motion, and prevent stiff joints.

Surgery is often the best option for serious nerve injuries. In the past, surgery was sometimes delayed to see if the nerves would heal on their own. However, new research shows that delaying surgery by more than 2 to 6 months could make the repair less successful. New imaging techniques can help your healthcare team decide when surgery would be most beneficial.

Nerve tissue grows slowly, so it can take many years before you see the final results of surgery. During recovery, you can do exercises to keep your joints flexible. Splints may be used to keep the hand from curling inward.

Types of surgery

- Neurolysis. This procedure is used to free up the nerves from scar tissue.

- Nerve repair. This involves directly repairing nerves injured by sharp objects, such as knives. Rarely, this can be done when nerve fibers are stretched.

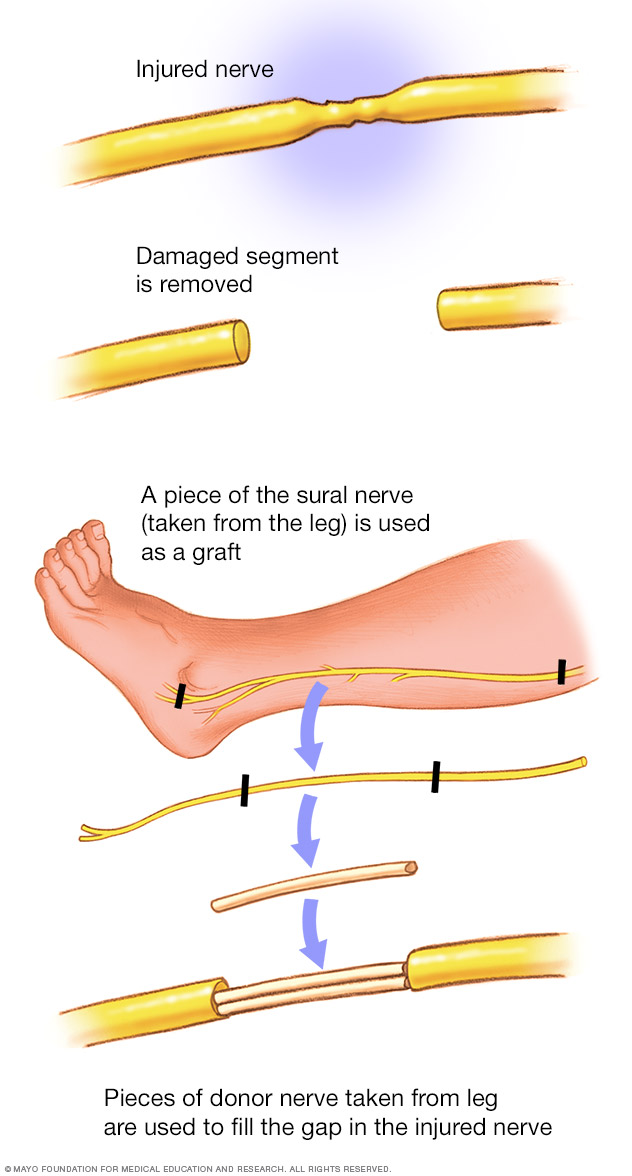

- Nerve graft. A nerve graft uses nerves from other parts of the body to replace the damaged part of the brachial plexus. This creates a bridge for new nerve growth over time.

- Nerve transfer. When the nerve root has been torn from the spinal cord, surgeons often take a less important nerve that's still working and connect it to a nerve that's more important but not working. This allows for new nerve growth.

- Muscle transfer. In muscle transfer, a surgeon removes a less important muscle or tendon from another part of the body, such as the thigh, transfers it to the arm, and reconnects the nerves and blood vessels to the muscle.

Pain control

Serious brachial plexus injuries can cause extreme pain. The pain has been described as a debilitating, severe, crushing feeling or a constant burning. This pain goes away within three years for most people. If medicine can't control the pain, your healthcare team might suggest surgery to interrupt the pain signals coming from the damaged part of the spinal cord.

Preparing for an appointment

Many tests may be used to help diagnose brachial plexus injuries. When you make your appointment, be sure to ask whether you need to prepare for these tests. For example, you may need to stop taking certain medicines for a few days or avoid using lotions the day of the test.

If possible, bring a family member or friend. Sometimes it can be hard to remember all the information you're given during an appointment. Someone who goes with you may remember something that you forgot or missed.

Other tips for getting the most from your appointment are:

- Write down all your symptoms, including how you were injured, how long you've had your symptoms and whether they've gotten worse over time.

- Make a list of all medicines, vitamins and supplements that you're taking.

- Don't hesitate to ask questions. Children and adults with brachial plexus injuries have many options for restoring movement. Be sure to ask your healthcare team about all the possibilities available to you or your child. If you run out of time, ask to speak with a nurse or have a member of your care team call you later.

© 1998-2025 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use